"Our to Master and to Own" - Julie Sherry - socialistreview

As the current economic crisis deepens, governments around the globe are attempting to force savage austerity measures on the working class. The argument about a different kind of society, one that is run and controlled by workers and in their interests, is now an urgent one.

Marx said that capitalism creates its own gravedigger - the working class. Our history is rich with lessons from past struggles when workers have challenged for power, sometimes confronting the bosses, sometimes confronting the capitalist state as a whole.

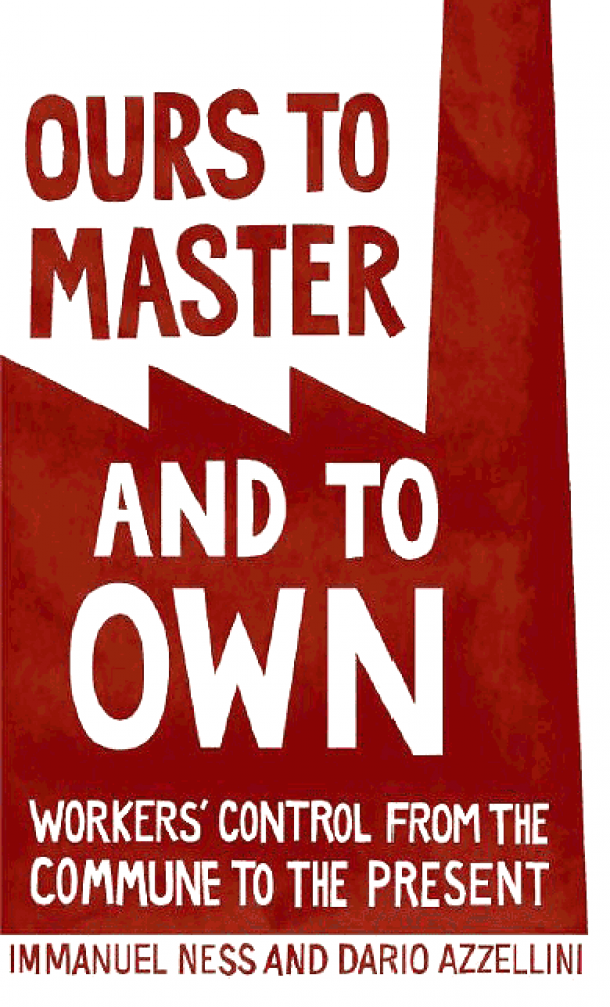

Ours to Master and to Own is an incredible resource. With 22 essays that cover over a century of struggle, it explores experiences ranging from soviet power in Russia, self-management in Yugoslavia and Algeria, workers' control in Portugal in 1974 and co-management in Venezuela today.

The book distinguishes between experiences that challenge the political and economic power of the state directly with workers' councils - such as the successful Russian Revolution, the failed German Revolution and the Turin factory occupation movement - and experiences of workers' cooperatives or co-management working within the capitalist framework, accepting the logic of profitability, as is the case in Venezuela today, for example.

The experience of Italy in 1919-20, recounted in Pietro Di Paola's essay, proves that the sustained existence of effective units of workers' power within capitalism is not possible. Once workers exerted their collective power and took control, they either had to challenge for state power or be defeated. The capitalist bosses would not tolerate such a threat to their hegemony within the system.

One of the key debates arising from the collection is on the role of revolutionary leadership. Victor Wallis criticises Lenin and the Russian Bolshevik Party for not giving priority to workers' control at every stage of its development, suggesting that the politics that led to the eventual loss of workers' power to Stalinism were inherent in the Bolshevik Party from as early as 1919-20.

Yet looking at the examples from Italy and Spain, it becomes clear that some form of leadership is needed. This is drawn out particularly well by Andy Durgan's essay on the revolutionary committees during the Spanish Civil War. The refusal of the anarcho-syndicalist CNT to seize power during the May Days of 1937 was in large part responsible for the defeat of the revolution.

Similarly in Italy, the refusal of reformist trade union leaders and the Italian Socialist Party to spread the Turin factory movement led to the movement's failure and its defeat precipitated the rise of fascism in Italy.

In both cases the lack of a sufficiently large revolutionary organisation left workers without a leadership that could direct it strategically towards success.

But crucially such leadership must act and organise as part of the working class. In an essay on Germany, Donny Gluckstein reminds us that during the Spartacist Uprising in 1919 revolutionary leaders such as Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht thought it was possible to bypass the workers' councils, rather than arguing within them for a position in support of the insurrection. This proved to be a fatal error.

Some of the most interesting articles come from less well known workers' struggles. One such example is provided by Jafar Suryomenggolo and considers the often forgotten workers' cooperatives in Indonesia following the anti-colonial revolution in 1945.

In East Java from 1945 to 1946 workers' cooperatives and farms were formed from redistributed land once owned by the old aristocracy. For some time neither the Dutch colonialists nor the British occupiers dared to go into East Java. Other articles on self-management in Yugoslavia, "auto-gestion" in Algeria and factory control in the US also help to tell the history of movements that have been overlooked in the past.

Although the experiments with workers' co-management and self-management within capitalism have shown repeatedly that workers are perfectly capable of running society, the examples from Europe following the First World War teach us a more important lesson.

They prove that if we want to see genuine workers' democracy and control, we need to transform society through challenging capitalism altogether. The historical examples also show that we need a revolutionary leadership that can develop a strategy to win. With the sheer scope of the examples, this book is a serious contribution to debates around workers' control, what is possible and how to achieve it. The chapter on 1970s British factory occupations should be mandatory reading for the period that is to come.