The Forgotten Workers’ Control Movement of Prague Spring

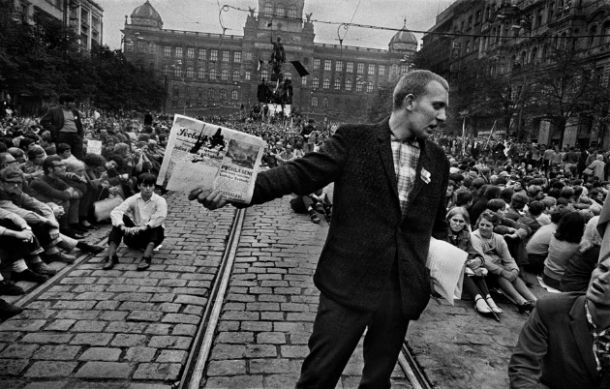

In his book, Pete Dolack retells the story of the workers' council movement in former Czechoslovakia that sprang up after the Soviet invasion in 1968.

At the time of the [August 1968] Soviet invasion [of Czechoslovakia], two months after the first workers’ councils were formed, there were perhaps fewer than two dozen of them, although these were concentrated in the largest enterprises and therefore represented a large number of employees. But the movement took off, and by January 1969 there were councils in about 120 enterprises, representing more than 800,000 employees, or about one-sixth of the country’s workers. This occurred despite a new mood of discouragement from the government from October 1968.

From the beginning, this was a grassroots movement from below that forced party, government, and enterprise managements to react. The councils designed their own statutes and implemented them from the start. The draft statutes for the Wilhelm Pieck Factory in Prague (one of the first, created in June 1968) provide a good example. “The workers of the W. Pieck factory (CKD Prague) wish to fulfill one of the fundamental rights of socialist democracy, namely the right of the workers to manage their own factory,” the introduction to the statutes stated. “They also desire a closer bond between the interests of the whole society and the interests of each individual. To this end, they have decided to establish workers’ self-management.”

All employees working for at least three months, except the director, were eligible to participate, and the employees as a whole, called the “workers’ assembly,” was the highest body and would make all fundamental decisions. In turn, the assembly would elect the workers’ council to carry out the decisions of the whole, manage the plant and hire the director. Council members would serve in staggered terms, be elected in secret balloting and be recallable. The director was to be chosen after an examination of each candidate conducted by a body composed of a majority of employees and a minority from outside organizations.

A director is the top manager, equivalent to the chief executive officer of a capitalist corporation. The workers’ council would be the equivalent of a board of directors in a capitalist corporation that has shares traded on a stock market. This supervisory role, however, would be radically different: The workers’ council would be made up of workers acting in the interest of their fellow workers and, in theory, with the greater good of society in mind as well.

By contrast, in a capitalist corporation listed on a stock market, the board of directors is made up of top executives of the company, the chief executive officer’s cronies, executives from other corporations in which there is an alignment of interests, and perhaps a celebrity or two, and the board of directors has a duty only to the holders of the corporation’s stock. Although this duty to stockholders is strong enough in some countries to be written into legal statutes, the ownership of the stock is spread among so many that the board will often act in the interest of that top management, which translates to the least possible unencumbered transfer of wealth upward. But in cases where the board of directors does uphold its legal duty and governs in the interest of the holders of the stock, this duty simply means maximizing the price of the stock by any means necessary, not excepting mass layoffs, wage reductions and the taking away of employee benefits. Either way, the capitalist company is governed against the interests of its workforce (whose collective efforts are the source of the profits), and by law must be.

National meeting sought to codify statutes

The Wilhelm Pieck Factory statutes were similar to statutes produced in other enterprises that were creating workers’ councils. It was only logical for a national federation of councils to be formed to coordinate their work and for economic activity to have a relation to the larger societal interest. Ahead of a government deadline to produce national legislation codifying the councils, a general meeting of workers’ councils took place on 9 and 10 January 1969 in Plzeň, one of the most important industrial cities in Czechoslovakia (perhaps best known internationally for its famous beers). A 104-page report left behind a good record of the meeting (it was also tape-recorded); representatives from across the Czech Lands and Slovakia convened to provide the views of the councils to assist in the preparation of the national law.

Trade union leaders were among the participants in the meeting, and backed the complementary roles of the unions and the councils. (Trade unions, as noted earlier, convened two-thirds of the councils.) One of the first speakers, an engineer who was the chair of his trade union local in Plzeň, said a division of tasks was a natural development: “For us, the establishment of workers’ councils implies that we will be able to achieve a status of relative independence for the enterprise, that the decision-making power will be separated from executive powers, that the trade unions will have a free hand to carry out their own specific policies, that progress is made towards a solution of the problem of the producers’ relationship to their production, i.e., we are beginning to solve the problem of alienation.”

Some 190 enterprises were represented at this meeting, including 101 workers’ councils and 61 preparatory committees for the creation of councils; the remainder were trade union or other types of committees. The meeting concluded with the unanimous passage of a six-point resolution, including “the right to self-management as an inalienable right of the socialist producer.”

The resolution declared,

“We are convinced that workers’ councils can help to humanize both the work and relationships within the enterprise, and give to each producer a proper feeling that he is not just an employee, a mere working element in the production process, but also the organizer and joint creator of this process. This is why we wish to re-emphasize here and now that the councils must always preserve their democratic character and their vital links with their electors, thus preventing a special caste of ‘professional self-management executives’ from forming.”

That democratic character, and the popularity of the concept, is demonstrated in the mass participation—a survey of 95 councils found that 83 percent of employees had participated in council elections. A considerable study was undertaken of these 95 councils, representing manufacturing and other sectors, and an interesting trend emerged from the data in the high level of experience embodied in elected council members. About three-quarters of those elected to councils had been in their workplaces for more than ten years, and mostly more than 15 years. More than 70 percent of council members were technicians or engineers, about one-quarter were manual workers and only 5 percent were from administrative staffs. These results represent a strong degree of voting for the perceived best candidates rather than employees simply voting for their friends or for candidates like themselves—because the council movement was particularly strong in manufacturing sectors, most of those voting for council members were manual workers.

These results demonstrated a high level of political maturity on the part of Czechoslovak workers. Another clue to this seriousness is that 29 percent of those elected to councils had a university education, possibly a higher average level of education than was then possessed by directors. Many directors in the past had been put into their positions through political connections, and a desire to revolt against sometimes amateurish management played a part in the council movement. Interesting, too, is that about half the council members were also Communist Party members. Czechoslovak workers continued to believe in socialism while rejecting the imposed Soviet-style system.

Government sought to water down workers’ control

The government did write a legislative bill, copies of which circulated in January 1969, but the bill was never introduced as Soviet pressure on the Czechoslovak party leadership intensified and hard-liners began to assert themselves. The bill would have changed the name of workers’ councils to enterprise councils and watered down some of the statutes that had been codified by the councils themselves. These pullbacks included a proposed state veto on the selection of enterprise directors, that one-fifth of enterprise councils be made up of unelected outside specialists, and that the councils of what the bill refers to as “state enterprises” (banks, railroads and other entities that would remain directly controlled by the government) could have only a minority of members elected by employees and allow a government veto of council decisions.

This proposed backtracking was met with opposition. The trade union daily newspaper, Práce, in a February commentary, and a federal trade union congress, in March, both called the government bill “the minimum acceptable.” In a Práce commentary, an engineer and council activist, Rudolf Slánský Jr. (son of the executed party leader), put the council movement in the context of the question of enterprise ownership.

“The management of our nation’s economy is one of the crucial problems,” Slánský wrote.

“The basic economic principle on which the bureaucratic-centralist management mechanism rests is the direct exercise of the ownership functions of nationalized industry. The state, or more precisely various central organs of the state, assume this task. It is almost unnecessary to remind the reader of one of the principal lessons of Marxism, namely he who has property has power…The only possible method of transforming the bureaucratic-administrative model of our socialist society into a democratic model is to abolish the monopoly of the state administration over the exercise of ownership functions, and to decentralize it towards those whose interest lies in the functioning of the socialist enterprise, i.e. the collectives of enterprise workers.”

Addressing bureaucrats who objected to a lessening of central control, Slánský wrote,

“[T]hese people like to confuse certain concepts. They say, for example, that this law would mean transforming social property as a whole into group property, even though it is clearly not a question of property, but rather one of knowing who is exercising property rights in the name of the whole society, whether it is the state apparatus or the socialist producers directly, i.e. the enterprise collectives.”

Nonetheless, there is tension between the tasks of oversight and of day-to-day management. A different commentator, a law professor, declared,

“We must not…set up democracy and technical competence as opposites, but search for a harmonious balance between these two components…It would perhaps be better not to talk of a transfer of functions but rather a transfer of tasks. It will then be necessary for the appropriate transfer to be dictated by needs, rather than by reasons of dogma or prestige.”

These discussions had no opportunity to develop. In April 1969, Alexander Dubček was forced out as party first secretary, replaced by Gustáv Husák, who wasted little time before inaugurating repression. The legislative bill was shelved in May, and government and party officials began a campaign against councils. The government formally banned workers’ councils in July 1970, but by then they were already disappearing.

Comments

Post new comment