Autoworkers Under the Gun: An Interview With Gregg Shotwell, UAW Activist and Author

Shotwell talks about the onslaught of auto management, the decline of the UAW and the efforts of autoworkers to resist both.

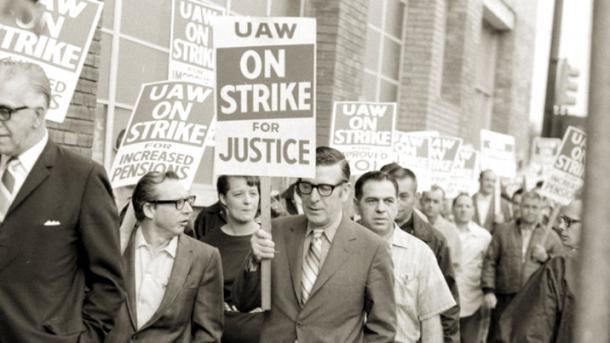

The sit-down strike by General Motors workers in the winter of 1936-37 was one of the galvanizing events in U.S. labor history. Similarly, the efforts of the primarily African-American autoworkers of the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement and the other RUM’s sparked the resurgence of rank and file militancy in the late 1960’s and 1970’s. In more recent years, the New Directions caucus and Soldiers of Solidarity carried on the radical tradition in the United Automobile Workers.

Gregg Shotwell was active in both New Directions and SOS for much of his 30 years working at General Motors during which time the UAW’s rolls fell from1.5 million members to 382,513. He published Live Bait and Ammo, a boisterous newsletter that regularly skewered management as well as official union passivity. Often hilarious, always biting and sometimes depressing, Live Bait and Ammo documented the devastating impact the collaboration between automakers and the UAW has had on workers in the factories.

Haymarket Books published a collection of Shotwell’s Live Bait and Ammo in Autoworkers Under the Gun: A Shop-Floor View of the End of the American Dream. In this interview, Shotwell talks about the onslaught of auto management, the decline of the UAW and the efforts of autoworkers to resist both.

Piascik: What was the situation in the auto industry and in the UAW when you began as an autoworker in 1979?

Shotwell: It was at that time American auto companies first started to experience serious competition from foreign automakers and they weren’t prepared for the contest. US consumers demanded fuel efficient vehicles and the American auto companies took advantage of the opportunity to upgrade their products by laying off hundreds of thousands of auto workers. In the best of times the companies took all the credit for success but when times got tough they put all the blame on workers and then proceeded to design some of the most notorious failures in auto history. Ralph Nader pilloried the Corvair but it didn't take Consumer Reports to bury the Vega, the Pinto, and the Gremlin beneath the irredeemable crust of US car history.

In the Eighties GM, Ford, and Chrysler were obsolete manufacturing enterprises. Rather than retool and revamp to make more competitive products, the companies took advantage of the situation to attack the UAW and blame poor quality and lackluster production on workers. The companies never relinquished what we called "paragraph 8" in the UAW-GM contract, or "management's right to manage." That is, management reserved the right not only to hire and fire but to design both the product and the means of production. Publicly, workers bore the brunt of the blame for GM's failure, but on the inside, pencil pushers made all the decisions.

In 1981, we started producing valve lifters for Toyota and the first batch we shipped was returned for inferior quality. Toyota taught GM how to produce first time quality products at our plant and I suspect at other GM plants as well. It wasn't magic. They simply raised the bar.

For its part, the UAW responded to the crisis of foreign competition by promoting hatred of brothers and sisters in other countries and encouraging UAW members to identify with the bosses.

Piascik: Were you involved in the union right from the start?

Shotwell: No. My initial response to the sensory assault of auto production —the noise, the smell, the relentless pressure to work faster and faster— was to drink alcohol. I wasn't alone but the addiction kept me undercover. It wasn't until I quit drinking that I began to get involved in the union. I needed to feel integrated in the workplace and getting active in the union helped me to feel like I was a part of a larger and more meaningful organization. I never would have believed it was the beginning of the end for the UAW.

Piascik: In Autoworkers Under the Gun, you talk about how workers had far more control of the shop floor 30+ years ago than now. Can you elaborate on that?

Shotwell: Automation and lean production methods, which are an intensification of Taylorism, have successfully sped up and dumbed down the jobs. In the Seventies, auto production required a lot more people power. Our sheer numbers gave us a greater sense of influence on the job and in society at large. Workers had more control over the production and pace of the work because manufacturing depended more on workers' knowledge, skills, and muscle.

Today, everything is automated, computerized, and heavily monitored. As a result human labor is devalued and workers feel less important. Thirty years ago, we also had a union culture that advocated confrontation rather than cooperation with the boss. There was a clear demarcation between union and management. In the Eighties, management attempted to blur that difference and the UAW went along with this ridiculous idea that the boss was your friend rather than someone who wanted you to work harder for less. It's been a painful history lesson and one that UAW President Bob King has failed to acknowledge despite the overwhelming evidence that concessions and cooperation do not save jobs.

In my early years, whenever management would start to crack down, we retaliated by slowing down production. The bosses learned quickly that if they wanted to meet production goals, the best way to do that was to treat the people who did the work with respect. If I was running production and the boss gave me a hard time, I would create a problem with the machine and write it up for a job setter, who in turn would shut it down and write it up for a skilled tradesman. When I told him the boss was on my back he would ask, "How long do you want it down?" This wasn't something that we organized, it was a part of the shop floor culture. We agreed never to do someone else's job, we had clear job definitions or work rules and we adamantly refused to violate our contract. Today, the UAW promotes speed up, multi-tasking, and job definitions or work rules which are so broad they are worthless. Workers today enjoy less autonomy because they have less support from the official union and a shop floor culture of cooperation rather than confrontation with management.

Piascik: Why, after so many years where "cooperation" with management has been so devastating to autoworkers, is the UAW pushing it harder than ever?

Shotwell: Because they are getting paid by the company. The Big Three (GM, Ford, Chrysler) set up separate tax-exempt nonprofit corporations which are managed by the company and the union but financed solely by the companies. It's a 501-c. As a result, salaries for UAW International appointees are subsidized by the company. The Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act (LMRDA) requires that unions make all financial records available to the membership, but these corporations are separate legal entities.

More generally, many unions, not the just the UAW, have lost their bearings. Union leaders don't have a world view independent of the corporations they serve. The institution of Labor is infected with opportunists who claim we can cure the afflictions of capitalism with a heavier dose of capitalism. As a result, union leaders advocate that we work harder for less and help the companies eliminate jobs. Competition between workers and cooperation with bosses is an anti-union policy, but it makes perfect sense to union leaders who have more in common with bosses than workers.

Piascik: You belong to an organization of rank and file autoworkers called Soldiers of Solidarity. What is SOS and what kind of work does it do?

Shotwell: SOS was a spontaneous reaction to an urgent crisis. Delphi hired bankruptcy specialist Steve Miller, who threatened to cut our wages 66 percent, eliminate pensions, reduce benefits, and sell or close all but five Delphi plants. The UAW didn't respond so I called for a meeting of rank and file UAW members to discuss what we should do to defend ourselves. Autoworkers and retirees from five states representing all the major automakers and suppliers came. They recognized that Delphi was the lead domino and if they took us down, the other companies would follow suit.

We agreed on the name Soldiers of Solidarity at our third meeting because we felt like we were engaged in a battle; we felt our struggle was not limited to the UAW or Delphi; the solution was solidarity; and the acronym was a distress signal. Initially, we decided not to focus on elections and internal union disputes because of the urgency of the crisis. A number of us had been in New Directions and we didn't want workers to think our idea of a fight back was electoral. We wanted to focus on direct action and work to rule. We understood that we were fighting the company, a cooperative union, and a capitalist government but we kept the focus on the company to attract as many workers as possible. We knew how ruthless the Administrative Caucus that controls the UAW could be but the Administrative Caucus was at the bargaining table and most members were pinning their hopes on them. As it turned out, the Administrative Caucus didn't waste any time attacking us anyway.

As a result, SOS was forced into behaving like an underground movement. We were in the shadows dismantling the apparatus of profit and threatening to take down the whole edifice of partnership if our demands weren't met. I said in one of my newsletters, "Management likes to throw money at problems. Let's give them a big problem to throw money at." We did. As a result, GM and Delphi, started meeting the primary needs of a majority of the members -- safe pensions, early retirement, subsidized wages and transfers back to GM. Workers made choices based on what was best for their families and resistance deflated. The downside to this guerilla defense was that we lacked a structure that could sustain us after the immediate crisis ended. SOS continued to advocate direct action but our numbers dwindled as so many chose retirement.

Piascik: How widespread is rank and file resistance to the union's collaboration with the companies?

Shotwell: There is a lot of dissatisfaction but actual resistance is minimal at this point. I think we have to bear in mind how fragile workers feel in the current economy. The government hasn't done anything to help create jobs, organize unions, or improve opportunities for working class people. Whenever there is a crisis for unions or working people in general, Obama is Missing In Action. If unemployment benefits are extended, it is always at the expense of the working class as a whole like with the extension of the Bush tax cuts.

I do believe, however, that momentum is building, primarily because the new generation of autoworkers doesn't have the golden handcuffs: pension and health care in retirement. The previous generation was bound to the company and the union by the promise of retirement after thirty years. Young autoworkers don't have anything to look forward to except a weekly paycheck and they are grossly underpaid for the work they perform. They have no reason to feel loyal to the company or the union that stabbed them in the back. As this new generation takes control -- and they will soon gain a majority in the UAW -- I believe we will see more resistance to the union's collaboration with the bosses.

Piascik: The 2009 auto bailout was much talked about, yet next to nothing was said in the mainstream media about how it furthered the attack on autoworkers. At the same time, autoworkers were said to be grudgingly accepting of the deal because the alternative was unemployment. Can you talk about this?

Shotwell: The 2009 bailout was, from a UAW member's perspective, extortion. We were told to accept it or lose everything we ever worked for. The general public was given the impression that UAW members were treated like prima donnas because they didn't lose their pensions, but none of the CEOs who engineered the calculated catastrophe lost their pensions. For some reason, Americans are led to believe that workers don't deserve contracts but no CEO in the nation will work without a contract replete with a golden parachute. Tell an auto supplier the contract is canceled and see how many parts you get on Monday. Contracts are the way capitalism works for capitalists, but workers aren't included in the legal equation.

Companies take the value generated by labor, transport it overseas, and then act like their pockets are empty. Labor has a legitimate lien on Capital. Companies routinely charge the customer more for the cost of doing business, as in the deferred compensation of a pension, and then spend the extra money on themselves rather than honor the contractual commitment. Bankruptcy is a business plan and a growing industry in the USA.

It seems outrageous that the government would give the companies so much money and not require a job program making worthwhile energy efficient products. Instead, the government gets company stock which binds the public to Wall Street rather than autoworkers, their natural allies, and union members get a contract that makes non-union an attractive option. Not only did new hires get half pay, they lost pension and health care in retirement -- about 66 percent of fair compensation. Then the extortion contract included a no-strike clause during the next set of negotiations which rendered collective bargaining a charade. The only people who had the stomach to watch 2011 auto negotiations were Right to Work for Less advocates and day traders making bets on the side. In 2011 traditional workers didn't get a raise in their pensions for the first time since 1953. Their pensions were effectively frozen and, considering how quickly new hires will be the dominant force in the union, I don't expect they will ever see a raise. But no one seems to notice the effect of a frozen pension on the future prospects of a workforce that can't conceivably work the assembly line until they are 66 or older. The Obama administration revealed its anti-union underbelly. Every reason that a non-union worker had to join the UAW is gone. Now Bob King is pretending that workers want the UAW so they can have a voice in the workplace. Whose voice? A UAW nepotistical appointee who thinks the boss is his bosom buddy?

Piascik: In your book you write, "The institutions - corporate, government, union - that brokered the self-destructive contrivance called neoliberalism are obsolete and need to be replaced." Union obsolescence seems to suggest that horizontal alliances between rank and file workers from different industries, as well as with community activists such as we saw to some extent in the Occupy phenomenon, is more the way to go than, say, the seemingly Sisyphean task of reforming a union or unions as a whole. What are your thoughts about this?

Shotwell: The so-called social contract has been broken and yes, I do believe that rank and file workers will have to decide whether the unions can be reformed, or if it would be better to organize a new union, one that included all workers. But that's a vision and I am not a visionary.

The building blocks of a revitalized labor movement are not in the sky. The building blocks are work units. In my experience struggle, not elections, is the fulcrum of change. Elections reinforce learned helplessness. Direct action reinforces the power that workers have over production and services and thus, profit. Likewise, demonstrations which may be inspiring and may be an organizing, agitating and educating tool are easily tolerated. Look how quickly and efficiently the government developed tactics to corral and disperse the Occupy protests. I agree with Joe Burns, author of Reviving the Strike that the best way to organize is with a strike. But I believe in this era of precarious employment the best strike method is on the inside.

The trouble with traditional strikes today is that union bureaucrats don't play to win. They use strikes to soften resistance and encourage compromise with management. One of the best examples of this was the UAW strike against American Axle in 2008, a time when American Axle was eager to reduce inventory. I felt that workers were set up to lose.

Whether one chooses to reform the union or start a new union, one must first organize workers. People work to support families, not ideologies. If you want to organize a workplace, fight the boss and win. Even a small victory is a building block. I was notorious for my criticism of the UAW. I called the bureaucrats the Rollover Caucus, the Concession Caucus, and eventually just the Con Caucus. But that didn't prevent me from working within the union, not only by attending meetings but by winning elected positions on the Local Executive Board and working on committees like Education and Civil Rights and By-Laws. These positions gave me access to knowledge and opportunities for new allegiances and influence. I think we have to use every tool in the box. Which reminds me of my favorite line by Ani DiFranco: "Every tool is a weapon, if you hold it right."

In the end I believe workers find that solidarity is not an ideal; solidarity is a practical solution to an urgent need.

Andy Piascik is a long-time activist and award-winning author who has written for Z Magazine, The Indypendent and many other publications. He can be reached at andypiascik@yahoo.com.