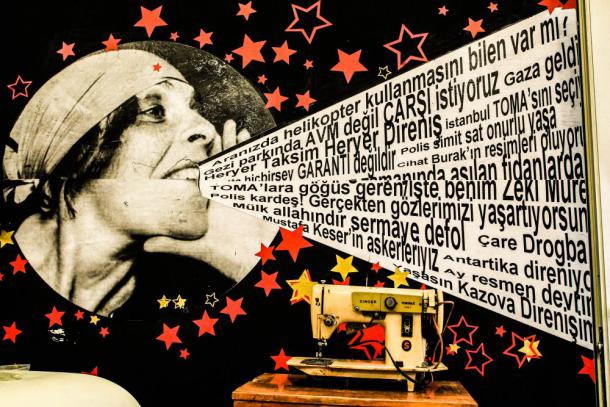

Kazova workers claim historic victory in Turkey

After two years of resistance, the Free Kazova worker cooperative in Turkey now started producing, setting an example for a new generation of workers.

"No, I didn’t receive any compensation, but I did get a factory,” was Aynur Aydemir’s response to one of her former colleagues from the Kazova textile factory, when she was asked if she had ever received any of the money their former bosses still owed them. “Whether it’s going to be successful or not, whether it’s old or new, I have a factory. We might lack the necessary capital to run this business, and we might fail in the future, but at least we got something.”

Aynur is a member of the small Free Kazova cooperative, which after two years of struggle finally managed to declare victory in February this year, when it was able to claim legal ownership over a handful of old, worn-out weaving machines which previously belonged to their former bosses.

During those two years Aynur and her colleagues had occupied their old workplace, were beaten by the police and threatened by hired thugs, led protest marches and fought in the courts as well as on the streets. While facing an uphill battle in which they had to take on not only their former employers but also the very system that enabled the exploitation of workers and allowed the bosses to walk away unscathed from every confrontation, the workers of the Kazova factory refused to lay down their arms. Instead they occupied. They resisted. And now, they produced.

To occupy, or not to occupy?

The Kazova workers’ ordeal started in January 2013 when, after not having received any payment for four months, they were collectively sent on a one-week holiday by the factory’s owners, the brothers Ümit and Umut Somuncu. The 94 workers were promised that their paychecks would be waiting for them upon their return, but instead they were received by the company’s lawyer who announced that they had all been fired because of their “unaccounted-for absence” for three consecutive days.

In hindsight, Aynur believes that if they would have refused to leave the factory from the very first day, their resistance would have been much more powerful. “We might not have been able to produce now, but probably we would have received our back pay,” she argues on a sunny terrace in Istanbul’s central Eyüp district, just outside the building where on the third floor her colleagues were busily working on the production of a fresh batch of brightly colored sweaters. “For the current situation it’s probably good that we left, but in the end 94 people lost their jobs without receiving any compensation.”

In the first few, chaotic days after their collective sacking the workers were indecisive about which steps to take next. Aynur suggested to occupy the factory, but she didn’t receive much support. Most of the workers were either too scared to resist or forced to waste no time protesting the injustice due to financial hardships. When in the end a group of thirty workers decided to resist, it was already too late to stop the plunder: the Somuncu brothers had stripped the factory of anything of value, including forty tons of yarn and several of the smaller machines, sabotaging the ones that were too big to move to prevent the workers from continuing production on their own.

When they realized what was going on, the workers set up a tent in front of the factory to prevent any further theft and sabotage. On a weekly basis they led protest marches from the central square in their neighborhood to the factory to demand attention for their cause. Over the next months they were beaten and intimidated by hired thugs and sued by their old bosses for stealing from the factory. When they staged a protest on May Day they were attacked and tear gassed by the police. The turning point occurred on June 30 when, emboldened by the country-wide Gezi protests, the remaining workers decided to occupy the factory.

A cooperative was born

The workers received an incredible amount of solidarity over the course of their resistance struggle. For Aynur this was one of the most important experiences: “I didn’t expect so much solidarity from the people, I had never seen such a thing before. I thought that some people would help us for a while and then disappear, but instead there was a constant flow of support.”

One of the thousands of people who visited the factory out of interest and to show their support was Ulus Atayurt, an independent journalist and researcher of autonomous worker movements. For him, the Free Kazova cooperative is an inheritance from the Gezi uprising, one of the few tangible results of the biggest popular uprising Turkey had ever seen. “I think the workers were inspired by leftists movements to set up the tent in front of the factory, but they were inspired by Gezi to take the next step and occupy the factory. The thousands of visitors and solidarity networks through the hundreds of people’s forums [which sprung up across Istanbul during the uprising] made them understand the power and meaning of a solidarity economy.”

Out of the fruitful mix made up of the spirit of Gezi, the many solidarity visits to the factory, the characters of the workers and people like Ulus — activists and researchers with knowledge of other examples of autonomous worker movements — the idea of a solidarity cooperative was born. Soon the remaining workers — by this time just a handful of the former Kazova workers were left — decided that they would organize themselves as a cooperative, and they started making plans on how to run their future factory without bosses.

What followed was a long and exhausting legal struggle in which the workers didn’t concentrate on retrieving the salaries their former bosses still owed them, but rather on the weaving machines that would allow them to start anew, to build up their own factory. This February, the machines went up for auction. A court had decided that the money from the sale of the machines had to be used to reimburse the duped workers. If any potential buyers failed to show up, the machines would be used for compensation. Naturally, the workers preferred ownership over the machines to their back pay — and so when the day of auction came and went without a single bid made, the workers celebrated the result as a victory.

Breaking the cycle

It has now been a few months since the Free Kazova cooperative has embarked on its adventure as one of the very few worker-run factories in Turkey. Although Aynur would be first to admit that it hasn’t been easy, she is intensely happy that she decided to have set out on this path. “I’m much more happy because nobody is insulting me anymore. We are realistic about the immense problems that we have and that are still on the road ahead, but at least we are no longer abused.”

Ulus, who has all but joined the cooperative and is helping the workers in setting up their distribution channels, experiences the difficulties the workers have in adjusting to these new labor relations on a daily basis. “On paper, self-organization, self-management and a democratic decision-making process sound good, but if you want to apply these on the workfloor, you realize that they entail a whole new set of relations that neither the workers nor us — the ones who are helping them — are used too.”

Aynur agrees that “a bossless organization is a burden of itself,” because of the collective responsibility which means that all decisions have to be made as a group. “We have to learn a life that we never knew before,” she adds with a smile betraying the challenge — one she is happy to accept.

By now the cooperative is producing 500 pullovers per month and selling them online and via a network of small boutiques. But in order to cover all costs, this number will need to be raised to 800 pieces per month. The workers take great satisfaction from the fact that are now in control of their own livelihoods and making profit is no longer on top of their agenda. Their ultimate aim is to become a role model for others: autonomous and independent, and an example for those who are currently trapped in a never-ending cycle of exploitation, insults and abuse.

Aynur, who perceives the current system in Turkey as favoring big capital at the expense of worker rights and general welfare, shares her dream: “we want that when it comes to our children, to their generation, that at least they have the kind of system that we are now trying to create.”

-----------------------------

For general inquiries, the Kazova factory can be reached at patronsuz@gmail.com. Orders can be send to info@ozgurkazova.org.

Comments

Post new comment