Array

-

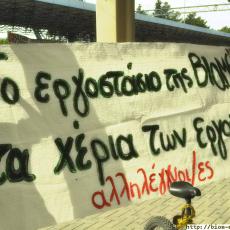

English22/02/13Workers of bankrupt daily 'Eleftherotypia' printed their own 'strike issue' in 2012 to raise money for the strike fund. This endeavour would eventually give rise to the cooperative 'Editors' Journal'.

Here it is! Done! The workers at Eleftherotypia, one of the biggest and most prestigious Greek daily newspapers, go forward undertaking the great endeavour of editing their own newspaper‘Workers at Eleftherotypia‘!

From Wednesday, Feb. 15th, kiosks all over the country are displaying one more newspaper next to the usual ones, a newspaper written by its own workers. This is a newspaper which not only aims at bringing the fight of Eleftherotypia’s workers to the fore, but also seeks to be a newspaper giving real information, especially at such critical times for Greece.

The 800 men and women workers at the firm H.K. Tegopoulos, which edits the Eleftherotypianewspaper, from journalists to technician staff, from cleaners to clerks and caretakers, have gone on continuous strike since 2011, Dec. 22th as their employer stopped paying their salaries in August 2011

Eleftherotypia workers, seeing that their employer has requested application of section nr. 99 of the Bankruptcy Act, in order to protect himself against his creditors, i.e. in reality his workers to whom he owes a total of approximately 7 million euro in unpaid salaries (!) have decided to have their own newspaper published, at the same time as continuing mobilisations and taking legal action. A newspaper distributed by news agencies all over the country, at the price of 1 euro (against the usual 1.30 euro for the other newspapers), in order to provide financial support to the strike fund.

As they haven’t been paid for the last seven months, the female and male workers atEleftherotypia are being subsided by a solidarity movement from various collectivities or even isolated citizens who donate money or make donations in kind (foodstuffs, blankets, etc.). By publishing their own newspaper and thanks to the money collected through its sales, they will be able to support their strike financially without any kind of mediation. In other words, they are making progress towards some kind of self-management.

The newspaper has been produced in a friendly workshop, in an ambiance that is reminiscent of clandestine newspaper editing, since the management, as soon as they found out that the journalists were going ahead with their publishing enterprise, first cut off the heating, then the system used by the sub-editors to write their articles, and last, shut down the workshop itself, even though access to the newspaper’s offices still remains free for the time being. Worker’sEleftherotypia was printed at printing works that do not belong to the company, with the support of the press workers’ unions, because the staff of its own printing works felt reluctant to occupy their work place.

The management, afraid of the possible impact of the self-managed publication of the newspaper, have threatened to take legal action; they are using intimidation by threatening to fire the editorial committee who were democratically elected by the general meeting of strikers.

However, Greek public opinion, and not only Eleftherotypia readers, had been eagerly waiting for its publication – we were overwhelmed by messages cheering the journalists for publishing the newspaper themselves – since dictatorship of the markets is coupled with media dictatorship that makes Greek reality difficult to read and interpret. Had it not been for the general consensus that was maintained by most media in 2010, based on the argument that there was no alternative to Papandreou government signing the first Memorandum, whose patent failure has now been acknowledged by everyone, we might have seen the Greek people rising up much earlier in order to overturn a policy that has proven disastrous for all Europe.

The case of Eletherotypia is not unique. Tens of private sector enterprises have long ceased paying their employees, and their stockholder have virtually abandoned them waiting for better times… In the press, the situation is even worse. Because of the crisis, the banks have stopped lending to companies while employers refuse to pay for it out of their pockets and choose to call on section 99 – at least 100 listed on the stock exchange companies have already done so – trying to save time in view of a possible bankruptcy of Greece and a probable exit of the euro zone.

Eleftherotypia was created in 1975 as “its sub-editors’ newspaper” during the period of radicalization that followed the fall of dictatorship in 1974. Today, in times marked by the new “dictatorship of international creditors”, Eleftherotypia’s women and men workers have the ambition to become the bright example of a totally different way of information, resisting against “terror” from the employers as well as the press lords, who would not like at all to see workers take in their hands the fate of information.

Originally publissed at Coalition of Resistance, reprinted from eagainst.com.

Moisis Litsis is an economic edito and a member of the Editorial Committee of “Worker’s Eleftherotypia”.

Efimerida ton Sintakton, Εργασιακή Διαμάχη, Moissis Litsis, Καταλήψεις Χώρων Εργασίας, 21ος αιώνας – Εργατικός Έλεγχος στη Σύγχρονη Εποχή, Ελλάδα, ΕυρώπηTopicΝαιΝαιNoΌχι -

German22/02/13Rezension von Christian Frings zu "Die endlich entdeckte politische Form"

Die letzten beiden umfassenden Darstellungen von Arbeiterräten und Arbeiter-selbstverwaltung stammen aus den Jahren 1971 und 1991. Ernest Mandel gab 1971 die Anthologie Arbeiterkontrolle, Arbeiterräte, Arbeiterselbstverwaltung heraus, die auch weniger bekannte Beispiele wie Seattle 1919, Bolivien 1953-1963, Algerien und Indonesien berücksichtigte. 1991 legte der Iraner Assef Bayat die Studie Work, Politics and Power – an international perspective on workers' control and self- management vor, die insbesondere den globalen Süden in den Blick nahm. Angeregt dazu hatte ihn die hier kaum wahrgenommene Arbeiterrätebewegung während der iranischen Revolution von 1979, die er in Workers and Revolution in Iran analysiert hatte. Dass nun auf Englisch und Deutsch eine weitere breit angelegte Textsammlung zu Fabrikräten und Selbstverwaltung erschienen ist, deutet auf das in der tiefen Jahrhundertkrise des Kapitalismus wiedererwachte Interesse an Alternativen zur profitorientierten Produktion hin, und es scheint auch kein Zufall zu sein, dass im letzten Teil des Buches zu Erfahrungen aus der Zeit 1990 bis 2010 die Beispiele aus Lateinamerika im Mittelpunkt stehen. Vor allem die praktischen Versuche der Übernahme der Produktion durch ArbeiterInnen in Argentinien sind – nicht erst durch Naomi Kleins Film The Take – weltweit zu einem Symbol für die Möglichkeit von Arbeiterselbstverwaltung geworden. Auf der großen Demonstration im belgischen Genk gegen die Schließung der dortigen Ford-Werke im letzten November kursierten Flugblätter, die eine Fortführung der Produktion in Eigenregie vorschlugen und dabei ganz selbstverständlich auf die Erfahrungen aus Argentinien hinwiesen.

Der vorliegende Sammelband, für dessen deutsche Ausgabe Marx' positive Beurteilung der Pariser Kommune von 1871 als Titel gewählt wurde – „Die endlich entdeckte politische Form“ – trägt eine ganze Reihe von gut bekannten, aber auch weniger bekannten Beispielen für die Kontrolle von ArbeiterInnen über die Produktion im 20. und 21. Jahrhundert zusammen. Die Herausgeber erwähnen ausdrücklich, dass sie keine Vollständigkeit beanspruchten, weshalb gerade für den lateinamerikanischen Kontext zentrale Beispiele wie die Bewegung der Cordones Industriales während der Regierungszeit Salvador Allendes 1970 bis 1973 in Chile oder der mit Rätestrukturen verbundene Arbeiteraufstand in der argentinischen Fabrikstadt Córdoba von 1969 fehlen (siehe zu diesen beiden Bewegungen die Artikel von Alix Arnold in der ILA Nr. 345 und 325). Die Herausgeber halten das Interesse am Thema aber für groß genug, um an einem zweiten Band zu arbeiten, der solche Lücken sicher schließen wird.

Die vorliegenden Beiträge im Buch sind auf sechs Teile verteilt. Im ersten behandeln vier Texte, die sicherlich zu den stärksten im Buch zählen, die historische und politische Bedeutung der Phänomene Arbeiterräte und Selbstverwaltung im Zusammenhang mit der Frage nach einer revolutionären Transformation der Gesellschaft. Der zweite Teil behandelt ihre Bedeutung „im Verlauf von Revolutionen“ im frühen 20. Jahrhundert (Novemberrevolution in Deutschland, Fabrikkomitees in der Russischen Revolution, Fabrikräte in Turin 1919/1920 und die spanische Revolution 1936/37). Zwei Beiträge zu Jugoslawien und Polen bilden den dritten Teil „Arbeiterkontrolle im Staatssozialismus“. Im vierten Teil werden Indonesien 1945/1946, Algerien, Mendoza (Argentinien) 1973 und Portugal 1974/1975 unter dem etwas unscharfen Titel „Antikolonialer Kampf und demokratische Revolution“ zusammengestellt. Der fünfte Teil besteht aus Beispielen, bei denen die Besetzung vor allem eine Kampfform und weniger den Versuch, die Produktion zu übernehmen, bildete: Großbritannien in den 70er-Jahren, die großen Sit-Down-Streiks Mitte der 30er-Jahre in den USA, der italienische „Heiße Herbst“ 1969 und ein spektakulärer Kampf von TelefonarbeiterInnen in Kanada 1981. Der letzte Teil „Arbeiterkontrolle 1990-2010“ besteht aus vier Beiträgen zu Indiens kommunistisch regiertem Bundesstaat Westbengalen, zu den besetzten Fabriken in Argentinien, der Arbeiter-kontrolle in Venezuela im Rahmen der „Bolivarianischen Revolution“ und selbstverwalteten Betrieben in Brasilien. Da die Versuche in Argentinien und Venezuela auch im deutschsprachigen Raum breit diskutiert werden (siehe auch die Artikel in diesem Schwerpunkt), soll sich im Folgenden auf eine Wiedergabe der brasilianischen Erfahrungen beschränkt werden.

In Brasilien beginnt die Geschichte von Versuchen der Selbstverwaltung schon in den 80er-Jahren mit „einer Reihe isolierter Experimente“, wie Maurício Sardá de Faria und Henrique T. Novaes in ihrem Beitrag „Die Zwänge der Arbeiterkontrolle bei besetzten und selbstverwalteten brasilianischen Fabriken“ schreiben. In den 90er-Jahren versuchen immer öfter ArbeiterInnen, vor allem in Familienbetrieben, die in die Insolvenz geraten, sie selbst weiterzuführen. In Brasilien wird diese Tendenz auch vom neuen Gewerkschaftsverband CUT unterstützt, der sich im Unterschied zum gewerkschaftlichen Verhalten in anderen Ländern solchen Versuchen der genossen-schaftlichen Produktion öffnet, statt nur um Abfindungen zu kämpfen. Als die mit dem CUT verbundene Arbeiterpartei PT (Partido dos Trabalhadores) unter Lula 2003 die Regierung bildet, erfährt dieser Prozess eine institutionelle Förderung durch die Einrichtung des Nationalen Büros für Solidarische Ökonomie (Secretaria Nacional de Economia Solidária – SENAES) beim Arbeitsministerium, deren heutiger Direktor der erste Autor dieses Buchbeitrags ist.

Ende der 90er-Jahre hatten sich die verschiedenen genossenschaftlichen Versuche, deren Schwerpunkt im industrialisierten Süden und Südosten Brasiliens liegt, in einem Verband der Kooperativen und Solidaritätsunternehmen zusammengeschlossen (União e Solidariedade das Cooperativas – UNISOL). Damit sollte u.a. das Unwesen der sogenannten Coopergatos bekämpft werden – Scheinkooperativen, die von den Unternehmern benutzt werden, um die Arbeitsverhältnisse zu prekarisieren. Dem Verband gehören heute etwa 280 Genossenschaften an, von denen zwar nur 25 selbstverwaltete Betriebe sind, die aber für 75 Prozent der Umsätze stehen. Es gibt zwar keine genauen Statistiken zu den besetzten und selbstverwalteten Betrieben, aber in einer Studie von 2005 wurden bereits 65 solcher Experimente mit 12 070 ArbeiterInnen untersucht. Wie auch in anderen Ländern hängt das Ausmaß der Demokratisierung und der Veränderung der Produktionsstrukturen stark davon ab, ob die Selbstverwaltung aus aktiven Kämpfen gegen die alten Unternehmer hervorgegangen ist und in welchem Maße diese Versuche mit breiteren gesellschaft-lichen Bewegungen verbunden waren. Insgesamt sehen die Autoren heute einen „Degenerationsprozess“ der genossenschaftlichen Bewegung, weil sich die Experimente zunehmend bürokratisieren. Die breiten gesellschaftlichen Kämpfe fehlen und auch in den aus heftigen Konflikten entstandenen selbstverwalteten Betrieben wird das Wissen um diese Kämpfe nicht an die Jüngeren weitergegeben. Es bleibe aber die Hoffnung, dass die Kooperativenbewegung in Brasilien im Zuge der neuen sozialen Auseinandersetzungen in der Krise und auch unter dem Eindruck der Versuche in Nachbarländern wie Argentinien mit neuem Leben gefüllt werde. Zur Veranschaulichung behandeln sie ausführlicher die zwei Betriebe Cooperminas und Catende Harmonia, die schon aufgrund ihrer Größe, aber auch wegen der um sie geführten Kämpfe „Sonderfälle“ bilden.

Die Minengesellschaft CBCA hatte 1917 die Kohleförderung in Criciúma aufgenommen und war Mitte der 80er-Jahre in die Krise geraten. Jahrelang kämpften die Bergarbeiter mit teilweise heftigen Aktionsformen, wie der Drohung, sich mit Dynamitstangen in die Luft zu sprengen, gegen die Schließung und Zwangsversteigerung der Mine. Sie erreichten schließlich 1997 die Übergabe des Betriebs und gründeten ihre Genossenschaft Cooperminas. In den ersten Jahren gab es eine funktionierende Versammlungsstruktur, an der sich fast alle der 1200 Bergarbeiter beteiligten, und sie führten deutliche Verbesserungen der Arbeits-bedingungen unter Tage ein. Aber auch hier setzt heute ein Bürokratisierungsprozess ein, weil viele von denen, die um die Eroberung des Betriebs gekämpft haben, bereits in Rente gegangen sind.

An dem Projekt Catende Harmonia ist vor allem interessant, dass es einen Land und Stadt verbindenden Versuch von „solidarischer Ökonomie“ darstellt. Im Bundesstaat Pernambuco hatte sich die 1829 gegründete Zuckermühle Milagre da Conceição in den 50er-Jahren zur größten Zuckerfabrik Lateinamerikas entwickelt – mit eigener Eisenbahnlinie, einem Wasserkraftwerk und ausgedehnten Zuckerrohrfeldern. Ende der 80er-Jahre geriet das Unternehmen in die Krise, 1993 sollten 2300 Zuckermühlen-arbeiterInnen entlassen werden. Zusammen mit den LandarbeiterInnen entwickelte sich dagegen ein breiter Kampf, und als 1995 die Insolvenz der Firma beantragt wurde, übernahmen die ArbeiterInnen die Kontrolle und starteten ihr Projekt Catende Harmonia, das etwa 4000 Familien mit 20 000 Personen umfasst. Neben 48 Zucker-mühlen und der Zuckerfabrik gehören dazu noch ein Wasserkraftwerk, eine Töpferei, eine Schreinerei, ein Krankenhaus, Staudämme und Bewässerungskanäle und eine große Fahrzeugflotte sowie mehrere der ehemaligen Herrenhäuser, von denen eines in ein Bildungszentrum umgebaut wurde. Nach sieben Jahren Projektarbeit konnte die Analphabetenrate von 82 auf 16,7 Prozent gesenkt werden. Auch wenn dieses Projekt heute unter gewissen Bürokratisierungstendenzen leidet, betonen die Autoren, dass es einen radikalen Wandel für den von der Zucker- und Alkoholproduktion geprägten Nordosten Brasiliens bedeutet, der immer noch starke Spuren von Zwangs- oder gar Sklavenarbeit aufweist. (zu Catende vgl. auch die Beiträge von Gert Eisenbürger in der ila 255 und von Astrid Schäfers in der ila 304).

Trotz seiner Unvollständigkeit und mancher Mängel in den einzelnen Darstellungen bietet das Buch umfassendes Material und viele theoretische Anstöße für die heute wieder aktuell gewordene Debatte um eine andere Welt und eine andere Produktion. Im Vergleich zu hiesigen Debatten um „solidarische Ökonomie“ ist vor allem begrüßenswert, dass die ArbeiterInnen und ihre Kämpfe hier als die eigentlichen Subjekte einer solchen Veränderung in den Mittelpunkt treten.

Dario Azzellini/Immanuel Ness (Hg.), „Die endlich entdeckte politische Form“. Fabrikräte und Selbstverwaltung von der Russischen Revolution bis heute, Neuer ISP Verlag, 540 Seiten, 29,80 Euro, ISBN 978-3-89 900-138-9Februar 2013

Αρχές του 20ού αιώνα – Εργατικά Συμβούλια και Εργατικός Έλεγχος κατά τη διάρκεια Επαναστάσεων, 1960-2000 – Εργατικός 'Ελεγχος ενάντια στην Καπιταλιστική Αναδιάρθρωση, Κριτικές Βιβλίων, Christian Frings, Άμεση Δημοκρατία, Εργατική Αυτοδιαχείριση, 21ος αιώνας – Εργατικός Έλεγχος στη Σύγχρονη ΕποχήMediaΝαιΝαιCurrent DebateΌχι -

English21/02/13Immanuel Ness and Dario Azzellini, eds.

Ours to Master and to Own is a compilation of articles offering a historical and global overview of workers’ efforts to gain control over their workplaces, the economy, and governance. It is wonderfully organized in both a chronological and thematic logic, from the nineteenth century through the early twenty-first century, while also moving from a general historical overview toward more specific explanations of how worker democracy was implemented and fought in

particular cases. The book sharply illustrates the struggle for economic demo- cracy, its various manifestations and possibilities, and the limitations posed by the larger context of internal political struggles in both capitalist and socialist nations. In their analysis, the authors take the view of rank-and-file workers as they seek to influence their working environment and community life. The essays bring out the various political interests which have undermined workers’ selfmanagement. The players include not only capitalist governments and employers, but in many instances also the authoritarian leaderships of socialist or communist political parties and labor unions. Under these conditions, workers’ efforts have usually been either unsuccessful or short-lived.The first part offers a historical overview of the revolutionary workers’ move- ments in Russia, Italy, Spain, France, Germany, and Britain through the first half of the twentieth century, with a brief reference to Chile in the 1970s. It illustrates the national and international political economy in each case, and their relation- ship with the ongoing debates regarding the best strategy toward a communal or socialized economy. The syntheses of these complex processes into various short articles are commendable, for they not only unravel the relationship between the various players but also address the theoretical visions that inspired the mobilizations. Although I felt frustrated by the broad sweep of the treatments, the implied longing for the visions in the movements, and missing references to the lived reality of the democratic process, this section offers a necessary overview of the political economy underlying the struggles and serves as the basis for understanding the more specific cases explored in the rest of the book.

Part II revisits the earlier movements, addressing the implementation of workers’ control in Germany, Russia, Italy, and Spain. The authors explore the organizational structure of the democratic workplaces and the battles for power between these new forms of organization and pre-existing ones, such as unions and socialist, communist, or social democratic political parties. These chapters make the history of Part I more tangible, yet still remain at the meso-level.

Based on two case studies, Yugoslavia and Poland, in Part III the authors illustrate the struggles for worker control under state socialism, showing the mechanisms through which the state retained control over the workplace, negating the workers’ efforts in self-management of not only their workplaces but also the economy.

Similarly, Part IV explores workers’ struggles for control in Java right after Indonesia’s independence (1945–46), Algeria in the 1960s, and Argentina and Portugal in the 1970s. In each of these cases, we are offered a brief historical context of either colonialism or military rule, an explanation of the factors conducive to self-management efforts, and an account of the political struggles leading to their demise. We gain a general sense of the organization of these nascent democratic structures, the threat they posed to leftist as well as rightist

powers, and the mechanisms through which those powers quelled the threat.We return to Europe and the United States in Part V, learning about workers’ struggles for control in Britain, the United States, Italy, and Canada. Alan Tuckman addresses British workers’ efforts beginning in the 1970s and moving through Thatcherism in the 1980s. Less known are efforts in the United States. Immanuel Ness offers a concise summary of such struggles, from workers’ mobilizations in the 1930s to their decline but continued efforts from the 1940s through the 1990s, closing with the well-publicized wildcat strike at Chicago’s Republic factory in 2008. Patrick Cuninghame narrates Italy’s Autonomia Operaia (Workers’ Autonomy) movement during the 1970s, illustrating the relationship workers in this movement had with council delegates, unions, and factory vanguards, as well as their direct action efforts, repression and defeat. Elaine Bernard tells the story of British Columbia telephone workers’ occupation in the early 1980s. This too is an inspiring case, where workers move away from the traditional strike as a weapon against the employer, instead taking over the production site while providing 186 Socialism and Democracy telephone service to customers. This detailed story of movement and countermovement nicely illustrates the capacity of workers to manage their workplaces very successfully, although briefly.

The last section brings the reader to efforts between the 1990s and the present. Arup Kumar Sen explores two labor struggles in West Bengal, addressing the possibilities and limitations of workers’ democracy in the context of a Communist-ruled state in India that functions within the national capitalist system. Marina Kabat, in her analysis of Argentina, highlights cooperatives’ role in sustaining a capitalist economy, noting that the government prefers the approach of worker buyouts – whereby workers take on the companies’ debts – over that of nationalization. Dario Azzellini’s article addresses the struggles for worker control in Venezuela, describing the government’s efforts to encourage worker ownership and self-management, and analyzing the mixed outcomes. Finally, Mauricio Sarda de Faria and Henrique T. Novaes address the experiences of recovered factories in Brazil, recognizing the key role unions have played in implementing selfmanagement.

A central theme in Part VI is the tension between two models, the cooperative enterprise versus the nationalized business run by its workers. While the authors tend to see cooperatives as manipulable to sustain the capitalist system, the democratization of nationalized businesses proves also somewhat elusive.

Throughout the book the authors grapple with two sets of battles: against the logic of capitalism and against the logic of the bureaucratic or authoritarian state. While the authors encourage readers to recognize the potential for self-management, for the most part the reader is left with a sense of defeat, as workers have not been successful in doing away with capitalism or bureaucracy. Missing are references to many micro-analytical case studies of the social relations of production, such as those exploring Mondragon, Beedi co-ops in India, Cruz Azul and Pascual in Mexico, and others. There is an underlying assumption that a market economy equates to capitalism, that there is only one interpretation of equality and fairness (equal pay for all kinds of work), and that the only way to overcome alienation is to end the division of labor. Many scholars who closely study alternative organizations of work question these assumptions; yet such challenges are not fully addressed in these articles, except for some passing comments in the last section.Nevertheless, this is a valuable text for undergraduate and graduate students who are becoming acquainted with the field, as well as for activists or practitioners. The cases open wonderful opportunities for further discussion regarding the paradoxes presented by the desire to have worker control – as suggested by the lack of interest or participatory culture among some workers, the potential and limitations of cooperatives compared to nationalized enterprises, and the clash between unions’ bureaucratic and oligarchic tenden- cies and workers’ search for participatory democracy. This collection also offers an excellent summary of workers’ efforts throughout the world to gain control over their workplace, economy and society.

© 2012 Sarah Hernandez

Division of Social Sciences - New College of Florida

shernandez@ncf.eduFirst published on Socialism and Democracy, Vol.26, No.3, November 2012, pp.185–188

ISSN 0885-4300 print/ISSN 1745-2635 online

Αρχές του 20ού αιώνα – Εργατικά Συμβούλια και Εργατικός Έλεγχος κατά τη διάρκεια Επαναστάσεων, 1960-2000 – Εργατικός 'Ελεγχος ενάντια στην Καπιταλιστική Αναδιάρθρωση, Κριτικές Βιβλίων, Sarah Hernandez, Εργατική Αυτοδιαχείριση, Εργατικός Έλεγχος, 21ος αιώνας – Εργατικός Έλεγχος στη Σύγχρονη ΕποχήMediaΝαιΝαιNoΌχι -

English21/02/13

"The Roman arena was technically a level playing field. But on one side were the lions with all the weapons, and on the other the Christians with all the blood. That's not a level playing field. That's a slaughter. And so is putting people into the economy without equipping them with capital, while equipping a tiny handful of people with hundreds and thousands of times more than they can use." (Louis Kelso in A World of Ideas, by Bill Moyers; Doubleday, 1990)

Can anyone any longer doubt that money and corporate power define the agenda of American politics? Can anyone seriously argue that if we fail to tame the economy, and bring it under democratic control, the 1% (more accurately the .1% or even .01%) will determine the fate of the planet and its people?

The agenda of our time should be to create voluntary associations as forums within which everyday people can discuss, debate, deliberate, argue, compromise, reflect, evaluate, learn, and powerfully act on their values and interests framed by a search for the common good, the public interest, and a blurred vision of the good society. Shared core values—those of the historic democratic tradition and of the justice teachings of the world’s great religious faiths—should frame a discussion that recognizes that all solutions are partial, that each presents new problems, that none are total, and that, in the words of the 1960s civil rights movement song, “freedom is a constant struggle.”

Worker Ownership and Control

This commitment to democracy is found in both Ness/Azzellini and Mathews, whose respective books are essential reading for anyone interested in how democracy might apply at the workplace. The former is an impressive collection of articles examining workers’ control as an expression of socialism and anarcho-syndicalism. Essays are both historical (spanning the twentieth century, and reaching into the first decade of the twenty-first) and international (the U.S., Soviet Union, Britain, Western and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America). Ness/Azzellini place worker ownership and control under the rubric of socialism.

Writers in the Ness/Azzellini collection are painfully aware of important nuances in the development of worker ownership: ownership without control; ownership in which old patterns of deference to authority—based on class, party, education and status—are maintained; ownership controlled by the state; ownership constrained by the vagaries of a market beyond the control of individual enterprises or even collections of them. They deal with the necessity of coordination beyond the enterprise level, the relationship of the state to the economy, the tendency toward parochialism and narrow self-interest that can arise in worker-owned businesses, and more. This is an important book.

A consistent Ness/Azzellini theme is criticism of vanguard parties and state control. In his “Worker’s Control and Revolution,” (Ness/Azzellini), Victor Wallis criticizes Lenin’s “disfavor to worker-control initiatives…In defense of [Lenin’s] stance, one can point out that many workers escaping the old [factory] discipline abused their freedom of action; however workers’ widespread heroism in the civil war suggests that if given meaningful opportunity [experienced managers would become “consultants”] the workers might well have acted differently.” The examples in the rest of the book testify to the realism of that possibility.

Mathews, on the other hand, wants to establish cooperativism as a “third way” between socialism and capitalism, and is particularly interested in its Catholic theological origins in the Encyclical Rerum Novarum and a subsequent expression—the Distributists. Their history is murky, including 1930s flirtations with Italian and Spanish fascism and with anti-Semitism. The intellectual origins of this theory are in “the prominent Catholic writers Hilaire Belloc and Gilbert Chesterton, together with—a little later—Gilbert’s younger brother Cecil Chesterton...all three were former socialists whose schooling in and around the socialist movement of the day enabled them to think their way through to a clear understanding of what sort of social reform made sense to them…[K]ey aspects of distributist thought were incorporated into new socialist philosophies such as guild socialism. The differences and tensions between the two camps, demonstrated in the ongoing debate on public platforms and in the weekly journals of the day, enriched both of them.” (Emphasis added.) This is an important book as well.

Mathews correctly identifies the beginnings of distributism in “an emergent synthesis between two more immediate reactions to poverty, namely those of British socialism as exemplified by the socialist revival of the 1880s, and the Catholic social teachings [of] Pope Leo XIII—acting in part at the instigation of the great British cardinal, Henry Manning,” and subsequently elaborated by the “personalist teachings of the prominent French Catholic philosophers, Jacques Maritain and Emmanuel Mounier.” His examples on the ground are the British Rochdale Cooperative Movement, the Nova Scotia Antigonish Movement, and “finally, by the ‘evolved distributism’ of the great complex of industrial, service and support co-operatives—now the Mondragon Co-operative Corporation (MCC)—which a remarkable Catholic priest, Don Jose Maria Arizmendiarrieta established in the 1940s and 1950s.”

Where Shall The Twain Meet?

It is astonishing to me that nowhere in Ness/Azzellini is there mention of the Antigonish Movement, Mondragon, Rochdale Cooperativism, guild socialism or GDH Cole, the latter’s principal theorist. Equally stunning is Mathews’s lack of reference to the rich experience and theoretical discussion present in Ness/Azzellini’s intelligent case studies.

Why? I believe the answer to this question is that down-deep these authors want worker ownership to serve a more overarching theory of how justice is to be achieved—socialism in the case of Ness/Azzellini and their collection of writers, distributism (cleaned of anti-semitism and fascism) in the case of Mathews, and capitalism in discussions of Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs)—where earnings are demonstrably greater in firms that combine employee ownership with employee participation in management. These tendencies exist despite the fact that the protagonists are all small “d” democrats. None is enamored of either a closed vanguard party, or of a theological or corporate elite who must guide the people to freedom or control them.

Are these different routes to worker ownership and control to remain in separate silos of conversation, or is there a way to bring the discussions together to strengthen each other? Can radicals, liberals, progressives, socialists, personalists, populists, social gospelists, small “c” capitalists or anyone else who cares about social and economic justice and popular participation (i.e. democracy) overcome the power of the present corporate and financial power elite without an affirmative answer, without constructing forums that bridge the silos? This is possible to achieve, as proven by numerous small “d” democratic organizers who have worked on the ground with faith in the capacities of everyday people and over the last hundred years have created the popular forums in which democratic power might be built, expanded, and enhanced.

Two Communist organizer/leaders of the Depression era, William Sentner in District 8 (St. Louis, Missouri area) of the United Electrical, Radio & Machine Workers (UE) and Herb March in the United Packinghouse Workers of America (UPWA), fought their own party when its dictates contradicted their democratic vision and commitment to their unions. They worked with Catholics, socialists, liberals, and other democrats to make their unions into democratic forums. On local matters each of them was generally able to beat down efforts from “on high” to tell them how to conduct union business. They contested “party discipline” and often beat it. Their experiences are detailed in Reuther, Zack and Balanoff/March.

The UE was expelled from the CIO as a “Communist-dominated” union. It survived the purge, along with the West Coast longshoremen’s union, ironically to be further weakened by the Communist Party. As James Lerner describes it, “The great reduction in UE’s membership, caused first by the McCarthy hearings and later by Communist Party efforts to break up the union in favor of the AFL-CIO merger, had devastating effects on the union’s bargaining strength.” The lesson of “ism” trumping small “d” democracy is well illustrated in his tale of UE; Reuther fills in details.

Herb March worked closely with Saul Alinsky in the development of the Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council (BYNC)—where the alliance of the union with local Catholic parishes, the Archdiocese, and small capitalists (i.e. neighborhood merchants and businessmen who extended credit during the duration of the packinghouse strike, and otherwise supported the strikers) was central to victory. Like Sentner, he fought against the Community Party for union democracy; he finally left the Party, he told me, over that struggle.

I am persuaded that Alinsky’s organizations, that sought to bring “everyone” in a broad constituency together under a common organizational umbrella so that they could unite behind a people’s program in a blurred vision of the good society and in opposition to any kind of centralized elite control, remain organizational forms from which important lessons for today can be drawn. Recall Victor Wallis’ phrase, “if given meaningful opportunity…” It echoes Alinsky’s idea of democracy, “given the opportunity, most of the time the people will make the right decision.” In a criticism of more current organizing, the extraordinary Chicago Catholic priest Msgr. Jack Egan asked me shortly before his death, “Mike, aren’t we supposed to get everybody in these organizations?”

Toward A Reframing

In a 2003 interview in the Communist journal, Political Affairs, noted playwright Tony Kushner was asked “about the crisis in theory…Do you think that the left feels it can’t proceed for lack of a grand explanation for moving forward…?” “Yes,” He replied, “Yes...I don’t know that a meta-theory can really ever have credibility again. I don’t know that it ever should…Any theory that seeks to explain all of history, and offers a single prescription for the incredible variety and the complexity of human behavior, has to rest on an oversimplification of people. Human beings are both communal beings and individuals, and to lose sight of one or the other is problematic…It’s the notion of economic justice, something like social justice, something like a recognition finally of the communal as well as the individual…powerful ideas that have persisted for centuries [with] great value in them” that are the overarching basis for moving forward. Those are ideas to be found in the Old Testament, Koran, Christian Gospels, and the secular Enlightenment tradition.

“All the problems of democracy,” Kushner says, “can only be solved by more democracy. If there is hope, it lies in a radical vision of democracy as a universal enfranchisement.”

For me, Alinsky’s “I don’t like to see people pushed around” combined with democratic values and practice, and careful analysis of current power relationships is sufficient. If others need grand theory, that’s o.k. But whatever the grand theory is, it needs to acknowledge that it doesn’t have a monopoly on the truth—and that democratic forums are needed to arrive at proximate truths, revise them based on experience, and continue on in the constant struggle for freedom and justice.

Mike Miller directs the San Francisco-based ORGANIZE Training Center. Reach him at www.organizetrainingcenter.org

Material discussed includes:

Ness/Azzellini: Immanuel Ness and Dario Azzellini, Ours to Master and to Own: Workers Control from the Commune to the Present (Haymarket Books, 2011); Mathews: Race Mathews, Jobs of Our Own: Building a Stakeholder Society—Alternatives To The Market and the State (Distributist Review Press, 2nd edition, 2009); Feurer: Rosemary Feurer, Radical Unionism in the Midwest, 1900-1950; (University of Illinois Press,2006); Lerner: James Lerner, edited by Richard Neil Lerner and Anna Marie Taylor, Course of Action: A Journalist’s Account from Inside (RNL Publishing, 2012); Targ: Harry Targ, “Herb March and Vicky Starr: Chicago Organizers of the United Packinghouse Workers of America (UPWA-CIO) (paper presented at the Working Class Studies Association, 2011 Conference, Chicago, Illinois); Balanoff/March: Elizabeth Balanoff and Richard March, Interview with Herbert March;” Roosevelt University Oral History Project in Labor History (November, 1970); Kushner: Tony Kushner, “Dramatic Revisions and Socialist Visions: interview with playwright Tony Kushner,” Political Affairs (January, 2003); Kelso/Hetter: Louis Kelso and Patricia Hetter, Two-Factor Theory: The Economics of Reality (Random House, 1967); Miller: Mike Miller, Mondragon: A Report From The Cooperatives in The Basque Region of Spain (Organize Training Center, 1994); and Schutz/Miller: Aaron Schutz and Mike Miller, People Power: Classic Texts in the Alinsky Community Organizing Tradition (Vanderbilt University Press, title tentative, 2013).February 20, 2012

Αρχές του 20ού αιώνα – Εργατικά Συμβούλια και Εργατικός Έλεγχος κατά τη διάρκεια Επαναστάσεων, 1960-2000 – Εργατικός 'Ελεγχος ενάντια στην Καπιταλιστική Αναδιάρθρωση, Κριτικές Βιβλίων, Mike Miller, Εργατική Αυτοδιαχείριση, Εργατικός Έλεγχος, 21ος αιώνας – Εργατικός Έλεγχος στη Σύγχρονη ΕποχήMediaΌχιΝαιNoΌχι -

English21/02/13

Workers' Control: Toward a Revolutionary Transformation

Virtually every crisis of modern capitalism from the late nineteenth century to today has been accompanied by workers' strikes, insurgencies and sometimes revolutions in which workers have taken over and run their workplaces. Workers took control of their factories through their strike committees, factory committees, and workers councils. Sometimes they did so in collaboration with a working class political party that was also fighting to create a workers' government, at other times they saw their workplace committees themselves as the government. Always workers fought the capitalist class of financiers, industrialists, and merchants, and sometimes they struggled with a socialist government or against a dictatorial communist state. Sometimes the experiments in workers' control, hamstrung by capitalist or state bureaucracies, were strangled in red tape and buried in government decrees. At other times, often in the most important cases, they were crushed by bloody counter-revolution. Almost always briefly, workers showed that they had the capacity not only to work, but also to manage a factory, and sometimes even to administer an industry. In the course of these all too brief experiments in workers' control, they showed how an entire society might be run differently, for the benefit of all and not only for the wealth and power of a few.

Now, in the first comprehensive volume since the nearly forty year-old Workers' Control: A Reader on Labor and Social Change, edited by Gerry Hunnius, G. David Garson, and John Case (Vintage, 1973), Immanuel Ness and Dario Azzellini have produced Ours to Master and to Own: Workers' Control from the Commune to the Present, a collection of essays by 23 authors describing a wide variety of these experiences of workers' control from a remarkable number of countries: France, England, Germany, Russia, Italy, Spain, Yugoslavia, Poland, Indonesia, Algeria, Argentina, Portugal, India, Venezuela, Brazil, Canada and the United States. In all of these countries between 1870 and 2010 we see efforts by workers to run everything from industry and agriculture to government offices and public services. When workers in the face of a crisis—economic collapse, war, or revolution—find themselves forced to reorganize production, they often also make it both more efficient and more humane, as well as more gratifying because they have taken ownership and control of the workplace. All of the essays provide fascinating accounts of workers' struggles for control while dealing with the particular historical realities of their time.

There are too many different experiences here to review them all, but we might mention a few: In David Mandel's essay "The Factory Committee Movement in the Russian Revolution," we see workers take control of their factories under capitalism, then play a part in a socialist revolution, and finally deal with the centralization of power by the newly founded Soviet State. In Andy Dugan's essay "Workers' Democracy in the Spanish Revolution, 1936-1937," dealing with the period of the civil war and the struggle between Francisco Franco's fascist Falange and the Spanish Republic, we see the anarchist workers of Catalonia decreeing and managing collective property under workers' control, as they face opposition not only from the capitalists but also from the Spanish Republican government. Jafar Suryomenggolo's essay "Workers' Control in Java, Indonesia, 1945-46," shows how the workers' control that emerged during the independence revolution against Japan and then the Netherlands became stifled by the new nationalist state. Samuel J. Southgate's essay "From Workers' Self-Management to State Bureaucratic Control: Autogestion in Algeria," presents a similar account of developments there following the Algerian revolution.

Today, as workers and those on the left are attempting both to create a new labor movement and a new conception of socialism, these essays challenge us to think about the complicated relationships between workers' rebellions, labor unions, workplace organization, political parties, and the state. These essays suggest that meaningful change will have to come from below, from democratic movements of working people in their workplaces, and that a fight for a democratic socialist society will have to be one that forces unions, parties and a genuinely democratic government to express the needs and desires of those working people. Sheila Cohen, author of one of the four introductory essays, hers titled "The Red Mole: Workers' Councils as a Means of Revolutionary Transformation," argues, as her title says, that the most important thing about all of these experiences is that they were the first step, the partial expression, the beginning of a revolutionary transformation. When workers begin to control their workplaces, the experiences recounted in this book suggest, it is also possible that working people might control the society and transform the government to create a truly human society.

Manny Ness has generously donated copies of this book to the UE Research and Education Fund in order to support the cross-border work of the United Electrical Workers (UE) and Frente Auténtico del Trabajo (FAT). For each tax deductible contribution of $25.00 or more, UEREF will send you a copy of this book.Immanuel Ness and Dario Azzellini. Ours to Master and to Own: Workers' Control from the Commune to the Present. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2011. 443 pages. Notes. Bibliography, Index. Paperback $19.

November 8, 2012

Αρχές του 20ού αιώνα – Εργατικά Συμβούλια και Εργατικός Έλεγχος κατά τη διάρκεια Επαναστάσεων, 1960-2000 – Εργατικός 'Ελεγχος ενάντια στην Καπιταλιστική Αναδιάρθρωση, Κριτικές Βιβλίων, Dan La Botz, Εργατική Αυτοδιαχείριση, Εργατικός Έλεγχος, 21ος αιώνας – Εργατικός Έλεγχος στη Σύγχρονη ΕποχήMediaΌχιΝαιNoΌχι -

English21/02/13

As I write this review, tens of thousands of people are engaged in Occupy protests and occupations around the world. Most famously in Wall Street, but also on the doorstep of the London Stock Exchange and in a hundred other locations around the globe. Workplace occupations have also been part of the recent struggles - here in the UK, in the last few years at the Visteon and Vestas plants. As this book ably documents, workers control, or at least workers management has been a feature of recent class struggle, as well as in the past. The revolution in Egypt is still developing, so it forms no part of the debates here. Perhaps a new chapter will have to be written soon.

Nevertheless, this collection of essays is extremely timely. Divided into several parts, the editors have collected articles to examine the full range of experiences. Some of the strongest articles are over-views of the historical process from a Marxist point of view. Of these, two in particular stood out. Donny Gluckstein's summary of the experience of Workers' Councils in Europe, based in part on his excellent book The Western Soviets looks at how workplace council's rose as out of revolutionary struggles, beginning with the Paris Commune and then the upheavels following the end of World War One. Similarly, Sheila Cohen's article looks at some of these events and those post World War Two in Europe, together with questions of the role of the State and alternatives to capitalism.

Several articles examine these processes in detail. Three look at the worker's council movement in Europe post World War One, examining Italy, Germany and Russia. The article on Germany is particularly interesting, as it looks at the question of workers organisation under the conditions of illegality, as well as the challenges posed by a young, immature shop-stewards movement faced with an explosion of revolution. It also rescues the fascinating and magnificent role of the workers leader, Richard Muller, who has been largely forgotten to revolutionary history. There are also superb chapters on obscure moments of working class history, Java and Algeria being two. One great strength of this book, is that it doesn't concentrate on the experience of workers in America or Europe, but draws on lessons from every corner of the globe, including near forgotten moments of our history.

These chapters are in my opinion some of the strongest. This is not because they are better written than the others, rather it is because the revolutionary period they cover is inspiring and offers real examples of alternatives to capitalism. The stories of how worker's ideas change at moments of mass revolutionary action is always inspiring and examples of how people take production into their own collective hands, overthrowing the boss and the manager and beginning to run society in their own interest are always useful.

Sadly, later chapters don't match these peaks. This is not simply because the subject matter is obscure. Their is confusion with the definition of workers control. For some authors, it is blurred between the potential for the revolutionary control of the means of production and any example of workers being involved in factory management. This later definition can often come from very top down initiative, such as the experience in Yugoslavia (the rather clunky titled chapter on "Self-Management as State Paradigm").

This is duplicated in later chapters on South America. Here worker's control and self-management have been taken to great heights by the state. Workers are encouraged to take control of their factories, managing them in the interest of the wider economy, yet without the bottom-up experience that marks the high-points of revolution. This is not to say the experience isn't positive. In Brazil, the reaction to bankruptcy of some industries has lead to "Recovered Factories" where despite the problems, it is "impossible to be indifferent after entering a factory like the former Botoes Diamantina... and watching the factory workers handling all different matters themselves, with the CUT flag hanging in the conference room."

However in many cases, the experience of taking over factories in economic crisis has proved difficult, if not impossible. A chapter on Venezuela points out many of the difficulties for such workers co-operatives. How much worker's control is there really when because "the state was the majority stockholder, all important decisions had to be approved by the ministry"? In response, the workers moved on from "comanagement" to workers councils, because, as one worker said, "we didn't kick out one capitalist to create 60 new ones". There is a danger, within capitalism, that isolated examples of workers management lead to a "market of solidarity" between such enterprises, struggling to survive without a further challenge to the status quo.

Despite this, even in the context of capitalism co-operatives challenge the priorities of the system. One characteristic of almost all the examples in the book is that when workers are given some control over their lives, they begin to change. The thrilling story of the Canadian telecom workers who, for five days ran the whole telephone company is a powerful story of how, by kicking out managers, work becomes more interesting, more fulfilling and the service improves. These workers learnt their own power, and because they could engage with others in the workplace, they understood their industry even better, learning about company jobs that they had never heard from before. This is the very beginnings of the old quote from Lenin, about how in the new workers state, "every cook should govern". The Canadian telecoms workers remained until forced out by the existing state and its legal apparatus, though the solidarity they received shows the potential for action even at low points in the class struggle (this was 1981). Their story is particularly of interest, because the strategy of occupation and control was used by a union that was considered weak and couldn't sustain the normal strike procedures.

It would be wrong to review such an important book without engaging in some slight criticism. One criticism I have is that in too few of the articles do we hear how the actual occupations, workers control or self-management worked. The Canadian story is one of the exceptions, but if we are to inspire a new generation of factory occupations and workers councils, we'll have to show how workers' democracy can work (warts and all) and how occupations might proceed. This book has too much of what the people at the top say and do, and too little stories from the ground. A few more quotes and recollections from participants would have helped enormously.

Finally, my main criticism is the old point about reform or revolution. For me, we look at workers councils in the past, to learn lessons about how to transform society in future revolutionary moments. The councils that sprang up from the bottom during the revolutions of 1917-1920, or those in Spain in 1936 or Chile, Portugal and others in the 1970s offer both a potential for a future society and lessons for us today. There is a danger that we see them as historical curiosities. Peter Robinson falls into this trap when he concludes his chapter on Worker's Control in Portugal, writing that it "was an extraordinary period, one that needs to be further studied and celebrated". Here Robinson makes the process sound like an abstract historical argument, rather than, as other chapters show, a living breathing debate that workers' in many parts of the world are engaging in today. As the recession deepens and the capitalists try to make workers globally pay for the crisis, its a discussion that millions more will take part in.November 11, 2011

Αρχές του 20ού αιώνα – Εργατικά Συμβούλια και Εργατικός Έλεγχος κατά τη διάρκεια Επαναστάσεων, 1960-2000 – Εργατικός 'Ελεγχος ενάντια στην Καπιταλιστική Αναδιάρθρωση, Κριτικές Βιβλίων, Εργατική Αυτοδιαχείριση, Εργατικός Έλεγχος, 21ος αιώνας – Εργατικός Έλεγχος στη Σύγχρονη ΕποχήMediaΌχιΝαιNoΌχι -

English21/02/13

Much recent discussion and scholarship has gone into dissecting the decline in the strength of the working class in the United States. For the most part, the emphasis has been on the steady weakening of trade unions and on excavating why union officials have been unwilling to attempt new forms of resistance. In such a context, discussions of workers control of the means of production—how it might look, what about it has succeeded and failed in the past, its relationship to revolutionary change—may seem a stretch. But maybe not. For perhaps what the U.S. working class needs as much as anything is to explore alternatives not only to neoliberalism but to traditional unionism, even that of the social movement type.

Ours to Master and to Own: Workers Control from the Commune to the Present edited by Immanuel Ness and Dario Azzellini goes a long way in assisting us in that exploration. Ness and Azzellini are well-positioned to put together such an important work; both have long radical histories as writers, teachers and activists. The result of their efforts is a rich collection of stories of workers seizing control of production in different epochs under a vast array of circumstances in numerous countries.

Councils, in a nutshell, are self- management organizations established by workers to administer production, usually in periods of great tumult. They may take shape in a single plant, in an entire industry or, in a revolutionary situation, in many plants and industries simultaneously. Through them, workers oversee all aspects of production including those which, under capitalism, are done by owners and bosses. The forms differ greatly but the common thread is that those who do the work should decide how it’s done.

There are two important themes that emerge as one reads through the cases collected by Ness and Azzellini. One is that many workers across time and around the world have understood better than any revolutionary theoretician that the working class controlling its own work is the way it should be. Second is that councils, apart from any trade union or vanguard party, develop spontaneously and organically as the system of private ownership slips into crisis. As detailed in the book, this development occurs so frequently in such instances as to be almost a natural phenomenon.

Ours to Master and to Own begins with four overview essays and follows with groups of analytical chapters in four categories. Significantly, stories of the global South are well-represented. Though far less industrialized than the North (and perhaps precisely for that reason), countries like Argentina and Venezuela are home to some of the most important contemporary experiments in workers control. With upheaval rocking much of the Middle East and Latin America, these case histories, together with those where councils were an integral part of anti-colonial insurgencies in Indonesia and Algeria, take on an additional timeliness.

Ours to Master and to Own also includes a number of familiar cases. Perhaps the three best known occurred in revolutionary (or at least what were perceived by some of the participants as revolutionary) situations: the soviets in Russia leading up to and immediately after 1917; the councils in Germany during World War I up to the unsuccessful uprising of 1919; and the anarchist-led movement in Spain in the 1930s. Each of these chapters is highly instructive, with nuanced analyses of the wide array of challenges the different groups faced. For the most part, each of these council movements failed simply because the forces aligned against them were too strong. However, there are valuable lessons within each that the contributing authors do an excellent job of mining.

Equally important are more recent cases such as Argentina during the economic crisis of 2001, compellingly summarized by Marina Kabat. Initially a response to neo-liberalism, the factory takeovers that helped topple President Fernando de la Rua took on a life of their own. As the takeovers evolved, workers grappled with how best to affect a degree of control within a capitalist society. No easy feat that, and many efforts failed or were coopted. As with the uprisings in the early 20th century, however, there is much in the experience of value. As Kabat writes of the takeovers, “an objective study of their characteristics and shortcomings will help remove obstacles and develop their complete potential for the future,” especially since “[t]he reprise of the economic crisis has opened new horizons for the taken factories.”

Other chapters of note are two from Eastern Europe—one on Yugoslavia by Goran Music and one on Poland by Zbiginew Marcin Kowalewski. Both document ongoing struggles for autonomy in societies purported to be workers’ states. The class conflict that surfaced quite dramatically in Poland in 1980 with the formation of Solidarity, for example, was the culmination of decades’ worth of work, rather than a brand new phenomenon. In Yugoslavia, Music relates the continuous contention between workers and the state over the form of self-management that lasted until the collapse of 1989.

Then there’s a fascinating case in India authored by Arup Kumar Sen where workers in a variety of work- places went head to head with a Communist state government within a capitalist society. Events unfolded much as those in other cases, and workers there faced many of the same obstacles. It would seem from so many examples that vanguardists are right in one thing and that is the revolutionary potential of the working class. That they often fear it and have frequently been—from Lenin and Trotsky forward—as hostile to it as any capitalist is one of the most important lessons of this volume.

Trade unions, including ones of the left, have also frequently opposed working class autonomy in the form of councils, especially at times of great upheaval. The period when fascism in Portugal was overthrown in 1974-75 is a prime example. As related by Peter Robinson, the alliance the Socialist unions forged with liberal military officials checked the possibility that the Revolutionary Councils of Workers, Soldiers and Sailors might expand their influence right at a point when something besides corporate liberalism was a possibility. Again, as we examine what was, we are left to wonder what might have been.

Still, the tone of Ours To Master and To Own is decidedly positive. In chapter after chapter, we can practically see workers contending with the most fundamental of revolutionary questions: what should the kind of society we want look like? How do we best get there?

Again and again, as events unfold, great emphasis is placed on process. In fact, in case after case, a successful outcome, however else that is measured, is inseparable from process. Workers went forward as often as not without deeply elaborated theories, but with a highly attuned sense that each was responsible to one another as well as to the future.

There is also much strategic discussion that is of immense value. In a revolutionary situation, for example, do councils pre-figure a working class state? Or does their consolidation mark the beginning of the end of the state? If the former, what should the relationship of the councils be to the state? Although some of the contributors put forward more decisive answers than others, the overall tone of the book is that these are still open questions to be answered with greater experience.

Inclusion of at least a few chapters authored by workers might have added another dimension to the book. Workers are quoted throughout and their insights are meaningful parts of a number of the analyses. Still, hearing summaries and perhaps some tentative conclusions from on-the-ground participants could have provided a larger understanding of the subject at hand.

The specific experiences of women in worker councils are also largely invisible in these accounts, perhaps because industrial work has been the domain of men and the councils largely the domain of the industrial work- force. Still, it would have been beneficial to hear about the role of women in at least a few of the case studies.

Though it is difficult to imagine any popular movement, working class-centered or otherwise, in which women would not play a prominent role, much of the work women do remains below the surface. It is for this reason that councils of the present and the future, at least those that are the most inclusive, may be influenced by cooperative economics with its emphasis on the citizenry at all levels—worker, domestic laborer, and consumer. At the same time, analysis that assumes the special role of women may bring into being more inclusive council formations.

The value of Ours to Master and to Own is that its contributors collectively wrestle with these kinds of big questions. Who should decide and which factors must be weighed in the deciding—are not questions with easy answers, after all. Ness, Azzellini, and all of the contributors have made a valuable contribution to our understanding of how to go forward. All the better that a second volume is in the works.

Andy Piascik is a long-time activist who has written about working class issues for Z, Union Democracy Review, Labor Notes and other publications.Αρχές του 20ού αιώνα – Εργατικά Συμβούλια και Εργατικός Έλεγχος κατά τη διάρκεια Επαναστάσεων, 1960-2000 – Εργατικός 'Ελεγχος ενάντια στην Καπιταλιστική Αναδιάρθρωση, Andy Piascik, Εργατική Αυτοδιαχείριση, Εργατικός Έλεγχος, 21ος αιώνας – Εργατικός Έλεγχος στη Σύγχρονη ΕποχήTopicΌχιΝαιNoΌχι -

English21/02/13

As the current economic crisis deepens, governments around the globe are attempting to force savage austerity measures on the working class. The argument about a different kind of society, one that is run and controlled by workers and in their interests, is now an urgent one.

Marx said that capitalism creates its own gravedigger - the working class. Our history is rich with lessons from past struggles when workers have challenged for power, sometimes confronting the bosses, sometimes confronting the capitalist state as a whole.

Ours to Master and to Own is an incredible resource. With 22 essays that cover over a century of struggle, it explores experiences ranging from soviet power in Russia, self-management in Yugoslavia and Algeria, workers' control in Portugal in 1974 and co-management in Venezuela today.

The book distinguishes between experiences that challenge the political and economic power of the state directly with workers' councils - such as the successful Russian Revolution, the failed German Revolution and the Turin factory occupation movement - and experiences of workers' cooperatives or co-management working within the capitalist framework, accepting the logic of profitability, as is the case in Venezuela today, for example.

The experience of Italy in 1919-20, recounted in Pietro Di Paola's essay, proves that the sustained existence of effective units of workers' power within capitalism is not possible. Once workers exerted their collective power and took control, they either had to challenge for state power or be defeated. The capitalist bosses would not tolerate such a threat to their hegemony within the system.

One of the key debates arising from the collection is on the role of revolutionary leadership. Victor Wallis criticises Lenin and the Russian Bolshevik Party for not giving priority to workers' control at every stage of its development, suggesting that the politics that led to the eventual loss of workers' power to Stalinism were inherent in the Bolshevik Party from as early as 1919-20.

Yet looking at the examples from Italy and Spain, it becomes clear that some form of leadership is needed. This is drawn out particularly well by Andy Durgan's essay on the revolutionary committees during the Spanish Civil War. The refusal of the anarcho-syndicalist CNT to seize power during the May Days of 1937 was in large part responsible for the defeat of the revolution.

Similarly in Italy, the refusal of reformist trade union leaders and the Italian Socialist Party to spread the Turin factory movement led to the movement's failure and its defeat precipitated the rise of fascism in Italy.

In both cases the lack of a sufficiently large revolutionary organisation left workers without a leadership that could direct it strategically towards success.

But crucially such leadership must act and organise as part of the working class. In an essay on Germany, Donny Gluckstein reminds us that during the Spartacist Uprising in 1919 revolutionary leaders such as Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht thought it was possible to bypass the workers' councils, rather than arguing within them for a position in support of the insurrection. This proved to be a fatal error.

Some of the most interesting articles come from less well known workers' struggles. One such example is provided by Jafar Suryomenggolo and considers the often forgotten workers' cooperatives in Indonesia following the anti-colonial revolution in 1945.

In East Java from 1945 to 1946 workers' cooperatives and farms were formed from redistributed land once owned by the old aristocracy. For some time neither the Dutch colonialists nor the British occupiers dared to go into East Java. Other articles on self-management in Yugoslavia, "auto-gestion" in Algeria and factory control in the US also help to tell the history of movements that have been overlooked in the past.

Although the experiments with workers' co-management and self-management within capitalism have shown repeatedly that workers are perfectly capable of running society, the examples from Europe following the First World War teach us a more important lesson.

They prove that if we want to see genuine workers' democracy and control, we need to transform society through challenging capitalism altogether. The historical examples also show that we need a revolutionary leadership that can develop a strategy to win. With the sheer scope of the examples, this book is a serious contribution to debates around workers' control, what is possible and how to achieve it. The chapter on 1970s British factory occupations should be mandatory reading for the period that is to come.October 2011

Αρχές του 20ού αιώνα – Εργατικά Συμβούλια και Εργατικός Έλεγχος κατά τη διάρκεια Επαναστάσεων, 1960-2000 – Εργατικός 'Ελεγχος ενάντια στην Καπιταλιστική Αναδιάρθρωση, Κριτικές Βιβλίων, Julie Sherry, Εργατική Αυτοδιαχείριση, Εργατικός Έλεγχος, 21ος αιώνας – Εργατικός Έλεγχος στη Σύγχρονη ΕποχήMediaΌχιΝαιNoΌχι -

English21/02/13Review of 'Ours to Master and to Own' by Immanuel Ness and Dario Azzellini (eds)

In Jean-Luis Cornolli’s film Cecília (a history of Giovanni Rossi, the Italian anarchist who built, with his companions, a libertarian community in the south of Brazil at the end of the 19th century) the main character speaks sublimely of comunità anarchica sperimentale. These communist principles ensured that common property and individual autonomy were guided by economic solidarity and mutually-constructed norms of living.

After a few years, political and personal internal conflict, aggravated by material difficulties and external repression by the authorities, provoked the end of the self-managed community. One of the leaders laments the failure but Rossi calmly retorts that they had proven that it is possible to live freely without bosses and working in a spontaneous way for the common good. Despite being short-lived, the experience had various lessons for advancing the search for freedom.

The social experiences analysed in Ours to Master and to Own illustrate this same principle: it is possible! It is possible to live without oppressive hierarchies and despotic authorities, and to live without petty competition.

Highly precarious institutional structures such as communes, workers’ councils, soviets, cooperative acts of resistance to factory/manufacturing discipline, factory occupations, self-management and so on are a dynamic proof of the role of work as an essential element in the construction of identity and social relationships. They demonstrate how cooperative workers are agents of the advancement of freedom. Their collective action attends to the interests of the whole of humanity, more so than initiatives by other agents.

The examples analysed here are varied, ranging from the classic European cases, the evolution of workers’ direct action in the United States and the experiences of the third world through to recent events in Venezuela and Brazil. This serious piece of work, put together by Immanuel Ness and Dario Azellini, deserves to be read alongside two other essential studies: Seymour Melman’s After Capitalism and Trabalhar o Mundo by Boaventura de Sousa Santos. Melman analyses the limits and possibilities of democracy in the workplace, exclusively in the US. Santos’s collection of work has a wider perspective, specifically considering cases in the global South.

Using different theoretical approaches and with distinct political orientations, these three pieces of work converge in their consideration of the inherent difficulties of libertarian action. These include internal difficulties, historical context and repressive politics, frustration and deadlock. But the authors also consider the achievements and the partial advances that have barred capitalism’s attempt to take complete control over hearts and minds.

The writers of Ours to Master and to Own point out new areas for debate, research and practical experiments, some of which are worth highlighting. These include the fact that, in general, direct action and attempts at workers’ control tend to occur as isolated experiments in just a few limited sectors of society. However, the transformation of society as a whole involves extending the democratisation of the workplace beyond isolated units.

In the wake of the bureaucratic degeneration and collapse of the Soviet system, the aim of many progressive activists today is no longer the construction of socialism, however it may be defined. Rather, it is the struggle for human rights, including the rights of ethnic and other minorities and the general expansion of the rights of citizens. Such formulations are well intentioned, but they are unable to present a comprehensive proposal for the transformation of the whole of society. In the absence of a comprehensive alternative, social movements are devoid of clear and defined objectives and an ideology that can bring together theoretical, historical and practical considerations. This condition manifests itself notably among organised structures, including left-wing parties and trade unions.

In the case of the unions, wage negotiations, working conditions and other such matters completely absorb the energy of activists. Such institutions carry out the role of modernising capitalist structures, without offering alternatives to capitalist exploitation.

Another area of debate and conflict lies in the relationship between any workplaces under worker’s control and society in general. A society that is socialised must be so in its whole, and not only in its individual units of work. But new structures have yet to be developed that can function on a society-wide level. Because of this, in the last chapter, Dario Azzellini analyses the experience of attempts at building popular communes for the modern era, such as those in the Venezuelan Bolivarian republic.

The social and environmental disaster that international capitalism has caused in the past 20 years reinforces the importance of this book. The alternative popular initiatives it describes are socially and economically far more advanced than the productivist and predatory canon of industrial capitalism. They are an antidote to the suicidal tendencies of high finance.

Workers’ control, self-management, economic solidarity and other forms of human economy are no longer merely possibilities for the achievement of utopia, but rather have become an imperative. It is necessary to put an end to the most negative trends of the dominant economics. It is necessary to overcome the mediocrity of conventional union action, and to recuperate work as an element of un-alienated human fulfilment.October 2011 (print and online versione)

Αρχές του 20ού αιώνα – Εργατικά Συμβούλια και Εργατικός Έλεγχος κατά τη διάρκεια Επαναστάσεων, 1960-2000 – Εργατικός 'Ελεγχος ενάντια στην Καπιταλιστική Αναδιάρθρωση, Κριτικές Βιβλίων, Antonio David Cattani, Εργατική Αυτοδιαχείριση, Εργατικός Έλεγχος, 21ος αιώνας – Εργατικός Έλεγχος στη Σύγχρονη ΕποχήMediaΌχιΝαιNoΌχι -

English20/02/13

Ours to Master and to Own: Workers’ Control from the Commune to the Present, by Immanuel Ness and Dario Azzellini – This book was one of those history books that leaves you feeling mad that you were not taught this information in school. There is such a rich history of worker councils, workers communes and worker owned enterprises that gives one hope that more of this could happen if we were just aware of it. The co-authors take us through the last 150 years to show that all over the world workers have been deeply committed to creating structures based on cooperation for the purpose of wanting more than just better wages. Worker run operations are also highly committed to different economic models, models that are in direct conflict with Capitalism. Ours to Master and to Own is an inspiring book that demonstrates we don’t have to follow the so-called free market model and attend business school in order to provide basic services for our fellow humans. This book can provide us with lessons on how we need to restructure our economic system that is not simply limited to buying local.

Grand Rapid Institute for Information Democracy, July 2011

Αρχές του 20ού αιώνα – Εργατικά Συμβούλια και Εργατικός Έλεγχος κατά τη διάρκεια Επαναστάσεων, 1960-2000 – Εργατικός 'Ελεγχος ενάντια στην Καπιταλιστική Αναδιάρθρωση, Κριτικές Βιβλίων, Jeff Smith, Εργατική Αυτοδιαχείριση, Εργατικός Έλεγχος, 21ος αιώνας – Εργατικός Έλεγχος στη Σύγχρονη ΕποχήMediaΌχιΝαιNoΌχι