Array

-

French10/07/11

Africascop est un film tourné au Burkina Faso en 2002 qui présente trois coopératives de producteurs du pays : « Garage tous unis » à Ouagadougou : atelier de réparation mécanique ; « Cotrapal » à Bobo-Dioulasso : production de jus et de fruits séchés ; « Zern-Staaba » à Po : tissage et couture.

Parmi les 65 organisées au sein de l’UCIAB (Union des Coopératives Industrielles et Artisanales du Burkina-Faso). Dans un pays ravagé par les politiques des Institutions Financières Internationales (FMI, Banque Mondiale…) qui poussent à la privatisation des quelques services publics existants et font la promotion d’une agriculture d’exportation au détriment des cultures vivrières, ces coopératives nous montrent comment la population, les travailleurs et les femmes de ce pays s’organisent pour maintenir les liens de solidarité essentiels pour une vie acceptable.

Il est d’ailleurs intéressant de voir comment le vieux principe démocratique de la coopération, « un individu = une voix », rencontre des traditions locales de solidarité qui ont favorisé le regroupement, notamment des femmes, pour susciter une activité économique, parfois de survie. Ce film montre, à cet égard, l’importance de la coopération internationale, certaines de ces coopératives fonctionnant essentiellement au travers des filières du commerce équitable.

Association Autogestion

10 juillet 2011

http://www.autogestion.asso.frFilm disponible auprès de Voir&Agir

Réalisation et images : Denys PININGRE Son : Issa TRAORE Montage : Catherine GALODÉ Auteurs : Denys PININGRE et Pierre GUIARD-SCHMID Production : Sophie Salbot (ATHÉNAÏSE) & Linda Ortholan (VOI Sénart) Avec le soutien du Centre National de la Cinématographie

Αφρική, Benoît Borrits, Συνεταιριστικό Κίνημα, Κριτικές Ταινιών, 21ος αιώνας – Εργατικός Έλεγχος στη Σύγχρονη ΕποχήMediaΝαιΝαιNoΌχι -

English31/12/09No bosses in sight at plants taken over by ex-employees in new workers' revolution in Argentina.

If Willy Wonka and Karl Marx went into business together the result might resemble Ghelco.

From the outside it is a nondescript industrial site in a drab suburb of Buenos Aires, the firm's logo barely visible. Inside, the first thing you notice is the smell of chocolate, honey, caramel, ice cream, cakes and jam. Machines hum while cheerful men in green overalls pack crates of confectionary.

The second thing you notice is the absence of bosses. There are no people in suits giving orders. They do not exist. Nor is there an official owner. Ghelco is run as a cooperative along democratic lines, with an equal say and equal pay.

"In the beginning no one thought we could do it, they thought we were brutes, ignorant. But we're still here, stronger than ever," said Daniel López, 37, who operates machinery and is a member of the sales team.

Welcome to the workers' revolution, Argentina-style. Ghelco is part of a movement where employees "recuperate" firms that have gone bust.

Marx urged workers to break their metaphorical chains but here they do it literally, breaking the chains and locks of their former workplaces, turning on the lights and restarting machines. Some 200 enterprises, from hotels to car parts factories, have started in this way, and now employ more than 15,000 people.

For some, the movement is proof of a viable alternative to neo-liberal capitalism. For critics it is an attempt to rewrite economic principles. For the workers it is a way to put food on the table. "This is not about ideology. It is about what works," said Luis Caro, a leader of the National Movement for Recovered Factories, an umbrella group representing 10,000 people at 80 factories.

The movement grew out of the economic crisis five years ago when Argentina defaulted on its foreign debt, triggering capital flight and the collapse of many businesses. Unemployment rose above 20% and nearly six in 10 sank below the poverty line. Ghelco's story is typical. The company laid off all 91 staff, leaving many owed months of back pay. "We were abandoned, we had nothing," said Juan Mellian. "So we took it back."

In early 2002 workers broke into the boarded-up premises. By begging in the street, then selling cardboard, they raised cash to fix machinery and buy cacao, sugar and other supplies. Water and electricity were reconnected after staff demonstrated outside utility firms with drums and firecrackers. Many white-collar staff did not return, thinking the effort doomed, so the machine operators were forced to manage the sales, marketing and accounting sides.

Five years later the factory is thriving. Each person in the 43-strong workforce earns £405 a month, more than double the previous salary, and the staff jointly make decisions at weekly assemblies.

Mr López, the machine operator, has bought his house, sends his stepdaughter to a private school, and his wife no longer needs to work outside the home.

The factory has earned the trust of suppliers and clients by paying its bills and improving quality control, he said. He attributed the higher salaries to the lack of "fat cat" executives.

In the past three years Argentina's economy has bounced back, easing unemployment and poverty. When a company goes bust there are alternative jobs available but workers often choose the potentially riskier route of taking over their old place of work. According to Mr Caro the Recovered Factories movement has almost doubled its membership in the past two years.

It is a radical, if pragmatic, cog in global capitalism, he said. Most cooperatives face a grinding battle for economic survival. Lack of investment capital and little sales or administrative experience are often crippling; many are in competitive industries, such as textiles.

Legal uncertainty also dogs the movement. While the government has approved a 20-year expropriation bill that frees factories from bankruptcy proceedings, no such exemption has so far been issued. The longest exemption given so far is for two years. "A lot of factories are still hanging in legal limbo," said Brendan Martin, director of Working World, a non-profit finance agency that lends to recovered factories.

The movement has been hampered by internal divisions, with some leaders finding politically radical allies such as militant trade unions. Others, such as Ghelco, have a lower political profile.

Neither the radicals nor moderates hold the political clout they did after the economic crisis. Arguably, the political dilution signals a step towards greater institutional and economic maturity. "Over the last few years we have really seen the movement shift from a political focus to a practical, production focus," said Mr Martin.

Those worker-led factories that are doing well tend to be in niche markets and have low infrastructure costs.

The 44 workers at Cortidoros Unidos Limitada, a wool and leather processing plant outside Buenos Aires, occupied their factory in March, three months after it shut, and are back to 10% capacity. A court has given them a year's grace to prove the cooperative viable. With the help of other cooperatives they are buying materials and paying their bills.

"I could probably have found a job at another company but I like this concept," said Salvador Fernández, 45. "To be your own boss. That's nice."

Reprinted from The Guardian, May 2007

Αργεντινή, Εργασιακή Διαδικασία, Ανακτημένες Επιχειρήσεις, Rory Carroll, Εργατική Αυτοδιαχείριση, 21ος αιώνας – Εργατικός Έλεγχος στη Σύγχρονη Εποχή, Λατινική ΑμερικήTopicΝαιΝαιNoΌχι -

English31/12/09Naomi Klein & Avi Lewis on "The Worker Control Solution from Buenos Aires to Chicago"

Shock Doctrine author Naomi Klein and Al Jazeera host Avi Lewis discuss the workers who are taking over their factories and plants rather than lose their jobs, some to owners who owe money to bailed-out banks. They also address the latest news in the nation’s global economic collapse amidst the White House and Democratic-led Congress’s rejection of single-payer healthcare. [includes rush transcript]

TRANSCRIPTThis is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.JUAN GONZALEZ: With the nation’s unemployment at 8.9 percent, the highest it’s been in over twenty-five years, workers across the country are fighting in a variety of ways to keep their jobs.

Nearly a thousand workers at the Chicago-based apparel firm Hart Schaffner & Marx, or Hartmarx, recently voted to “sit in” to save their jobs in an effort to prevent Wells Fargo from liquidating the factories.

In December, at the Republic Windows and Doors factory in Chicago, workers occupied the factory floor after the plant’s owners gave employees just three days’ notice of the plant’s closure. The workers ended their six-day occupation after winning a settlement securing the reopening of the plant under new management.

AMY GOODMAN: Later in the show, we’ll be joined by Armando Robles, a union leader and maintenance worker at the former Republic Windows and Doors factory.

But first, we turn to journalists Naomi Klein and Avi Lewis. In 2004, they produced the documentary The Take about workers in Argentina taking over the factories abandoned by their owners. Naomi is author of a number of books, including The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism and No Logo. Avi Lewis is the host of the news show Fault Lines on Al Jazeera English. They’re speaking tonight at Cooper Union here in New York at an event called “Fire the Boss: The Worker Control Solution from Buenos Aires to Chicago.”

We welcome you both to Democracy Now! Naomi, before we go into these various takeovers from Argentina to Chicago, your comment on the latest situation with the banks? We haven’t seen you since, well, soon after the various bailouts.

NAOMI KLEIN: And they’re ongoing. I mean, I wish things had gotten better since we last spoke. And I think I called the bank bailout the biggest heist in monetary history back then, and it’s just gotten bigger. We’ve seen just an absolutely unprecedented transfer of public wealth into private hands. And, you know, what I’ve been saying from the beginning, I think it’s becoming even clearer now, which is that the crisis in the financial sector is not being solved, it’s being moved. A private-sector crisis is being transformed into a public-sector crisis, in the sense of the huge deficit that’s being left behind because of this bailout, which isn’t even doing what it’s supposed to be doing in terms of restoring credit and fixing the real economy.

So the price of this is — if it isn’t fixed, is going to be paid in cutbacks to healthcare, to Social Security. We aren’t even — we haven’t felt the full shock yet. And that’s my concern. Yes, I’m concerned about what’s going on now, but I’m concerned about how this transfer of wealth is going to be paid for down the road in terms of the meager social services that Americans get in exchange for their tax dollars.

JUAN GONZALEZ: Well, and yet, you’re seeing now, at least in the stock market, the bank stocks, as well as some of the others, at least leveling off or beginning to rise again, even as unemployment continues at record levels, new people that are thrown out into the street every month.

NAOMI KLEIN: You know, and during the election campaign, you know, I think what Obama articulated so well is the fact that people realize that what’s good for Wall Street isn’t necessarily good for Main Street. And he said, you know, we’ve had this top-down approach, giving more and more to people at the top, waiting for it to trickle down, and he promised that that would change.

Quite the contrary. What’s actually happened is that homes, jobs have been sacrificed in order to stabilize the financial sector.

So what I’m really worried about is that what we’re seeing, if this, quote-unquote, “works” — and, of course, that’s up for debate, and we have some very respected economists, like Joseph Stiglitz and Paul Krugman, who have said very clearly that they don’t even think this is going to save the financial sector, that we don’t — we haven’t even addressed the depth of that crisis, because we don’t even know the extent of the toxic debts. But even if it does work, you know, even if we suspend disbelief and believe that it does work, what I’m worried about is that this is the new normal, that the banks are being saved on the backs of union workers, on the backs of what’s left of the manufacturing sector, on the backs of homeowners. And so, what becomes the new normal after the crisis is an even more deeply divided country, an even more de-industrialized country.

And that’s why we’re highlighting tonight, in this event that we’re doing at Cooper Union, and bringing in workers who are on the frontlines of this struggle to tell their stories of how they’re trying to save their workplaces, is that, you know, we need to address this now, because this is — we don’t want this to be the new normal.

JUAN GONZALEZ: I wanted to ask you, because you seem to be focusing more on how workers and ordinary Americans can respond themselves, but we’ve seen, for instance, the Service Employees International Union, SEIU, launch this huge corporate campaign against Bank of America to get the union and citizen groups to get involved and trying a shareholder revolt to remove Ken Lewis. I reported at theDaily News that SEIU, while it was doing that, was also increasing the amount of money it personally, the union, was borrowing from Bank of America.

NAOMI KLEIN: Yeah.

JUAN GONZALEZ: And — but this effort to direct the struggle toward shareholder actions rather than actual grassroots organizing in these communities?

NAOMI KLEIN: Well, you know, that’s why I think that the case of the Republic Windows and Doors factory is so interesting — and, you know, looking forward to hearing from Armando later in the show — is that I think it is really important for the labor movement to talk about the injustice of the bailout, to do a huge amount of popular education, but for me, it’s less about changing the CEO at the top and more about highlighting the incredible double standards. And that was why the Republic Windows and Doors occupation became such a — not just a national symbol, but an international symbol, because the workers in that factory, with their union leadership at UE, which is a smaller, very democratic union, decided that they were not just going to highlight the actions of their bosses, the owners of their factory, but the actions of Bank of America, in the fact that they had gotten bailout money and that they had refused a line of credit.

So, here you had, you know, the country in an — outraged over the fact that so much taxpayer money had gone to these banks, in the name of increasing credit, and then they’re finding out that the banks aren’t actually lending. But here you have this very concrete case where the banks didn’t lend to a workplace that needed it, the workers were paying the price, and so here you had the sort of injustice, the double standards of the bailout, and their slogan, “You got bailed out; we got sold out,” you know, in microcosm.

So I think that, to me, that is a much more — a better use of the targeting of the banks than changing the — going after, you know, the CEOs at the top, because I think we have this illusion that when you change the CEO, then something deep is happening. And that becomes almost synonymous with re-regulation, which is what we really need in the financial sector. And if we think back to the ’30s, you know, in FDR’s first hundred days, he got Glass-Steagall passed. We’ve seen no serious re-regulation of the financial sector. And so, when we just focus on changing the leadership and that kind of shareholder activism, I think we have the illusion that there is a sort of real re-regulation going on in the financial sector, and it’s just not happening. And that’s what we need the labor union — labor movement to be saying.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, before we go to Chicago and Argentina, Avi Lewis, I did want to ask you about, well, the industry that isn’t getting quite as much as the banks. That’s the auto industry. And you’re just back from Detroit. Chrysler announcing plans to close, what, nearly 800 dealerships, a quarter of its retail chain; General Motors is expected to follow suit today with closing a thousand dealerships. Taken together, it could mean something like 90,000 workers will lose their jobs.

AVI LEWIS: Well, I just spent a week in Detroit doing the latest episode of Fault Lines on the auto crisis and the way it’s being experienced on the ground by workers in where the auto sector used to have its home. What’s fascinating about what I learned, that is not being talked about right now, has to do with the financialization of the auto sector and of all American corporations and the way that that is now taking a real hit out on working people.

So, you have, in the stress tests, remember, one of the biggest insolvencies that was revealed was the financing arm of GM, GMAC, which has an $11 billion hole in its balance sheet, which the public is going to backstop, which we’re going to pay for, because — and this is what’s not being told — GM, the credit arm, and the Ford credit arm, in different degrees, and Chrysler’s, too, were gambling in derivatives, because there were super profits to be made when the bubble was being inflated. We have a lack of productive investment in the auto sector, which has been going on for three decades, while they’ve been financializing.

So you see immediately the Treasury Department is prepared to bail out the financial arm of GM, while GM and Chrysler are both being forced into bankruptcy. So, not only do you have the financialization of the sector and the bailouts for the financial arms, which dwarf the others, you also have the logic of the vulture capitalist at work in the auto sector.

Why are they being driven into bankruptcy? Why is there such a rush to go into the bankruptcy process? I interviewed Ralph Nader, who’s been following the auto industry for a little while now, and he said that basically it’s about driving — it’s speculative capitalist logic to drive the companies down to get — to squeeze what can be squeezed — unemployment and layoffs always rise a stock price — to cash out on the bounce back.

If you look at the Auto Industry Task Force that President Obama has appointed, there’s no one from the auto sector there. Most of them are investment bankers, and they’re looking at this as a classic corporate restructuring, where you’re focused on the share price, where you’re focused on the bounce back, where you’re getting billions of dollars of public money. Jobs are just simply not the focus there. So the auto industry is subject to some of the same special treatment when it comes to the financing arms, but to a very different standard when you’re talking about the actual workers.

And so, that’s why we’ve seen worker occupations in the auto sector, too. In Canada, there have been four plant occupations in the last four months, I think, all of them plants that were closed suddenly and abruptly without the proper notification; severance packages, which are up in the air, maybe drifting away; and workers leaping to their feet in this moment and saying, “Wait a second. There’s trillions of dollars of public money, which are being —- which is being funneled to certain kinds of businesses. Where’s our bailout?” That’s a powerful call.

JUAN GONZALEZ: But yet, some of the Republican critique of the bailout crafted by the Obama administration of the auto industry is that Obama is favoring the unions and the workers, that, in essence, now the UAW will end up, for instance, in the Chrysler situation, as one of the main owners of the new company.

AVI LEWIS: Well, you know, now we’re talking about healthcare. Now we’re talking about single-payer healthcare, and I’ll tell you why. It costs the Big Three $1,500 more per car in healthcare costs alone than their rivals, who are either working in countries like Canada that have universal healthcare or who aren’t subject to those costs, like the Japanese automakers. So, they -—

AMY GOODMAN: So, they pay more for healthcare than they pay for steel.

AVI LEWIS: Exactly.

AMY GOODMAN: They can’t compete with the foreign companies —-

AVI LEWIS: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: —- because they’re from countries that have single payer.

AVI LEWIS: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: And you’re from Canada, which is very interesting. You have an interesting perspective.

AVI LEWIS: Well, one of the reasons that the auto industry has been so strong in Canada all these years is that, you know, it’s so much cheaper for the Big Three to do production just over the river, you know, in Windsor, from Detroit, because those healthcare costs are covered by society rather than by the companies.

So when we talk about the UAW owning half of the new Chrysler or half of the new GM, we’re not actually talking about worker ownership or, let alone, worker management. They’ll only get one seat on the board. What we’re talking about is the $20 billion, for instance, that GM owes to workers in healthcare obligations. They’re getting half of that in cash, and they’re getting half of that in stock of the next company.

So the union is gambling that the new company will do well enough that it will be able to honor the healthcare obligations to its own workers, which GM always had contractually, which the union exchanged and agreed to manage as part of decades of concessions. And now, it’s the United Auto Workers health fund which will own half of the new company. That’s a gamble, that the new company will be strong enough to pay for healthcare obligations, which should have been universalized a long time ago.

NAOMI KLEIN: You know, I just would just add, you know, that clip that you played earlier of Obama saying, you know, we’re not starting from scratch — true, no country is ever starting from scratch. But when you look at the way all of these various crises are interrelated, the healthcare crisis with the financial sector crisis with the manufacturing sector crisis, you could not imagine a moment when there — which was more ripe for possibility of actually stepping back and going, “This whole thing is broken; how do we rebuild this in a way that makes sense?” There’s not going to be another moment like this, Amy, you know?

AMY GOODMAN: And that’s interesting that they’re not questioning nationalizing the debt of — and bailing out these banks and these other companies, like AIG, but they question nationalizing the cost of healthcare, which involves everyone.

NAOMI KLEIN: Yes, that this — they agree with the Republicans: that would be socialism. So, yes, it’s true. Avi and I are from a socialist — the socialist country of Canada, would that it were so.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to Naomi Klein and Avi Lewis. Avi works at Al Jazeera, does a broadcast called Fault Lines on Al Jazeera English. And he is the director of The Take, which Naomi Klein made also, about Argentina. When we come back, we’re going to go to Chicago to find out about the takeover of a factory, and we’ll also be going to Argentina. This is Democracy Now! Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to go to Chicago and then to Argentina to look at these takeovers of plants. Our guests, Naomi Klein and Avi Lewis. But, Avi, can you just give us an overall summary of what’s happening with these plant takeovers around the world?

AVI LEWIS: Well, I mean, as much as financial bailouts and financial crisis gets covered, we get unemployment numbers, we get fewer faces, but the crisis is people are losing their jobs in staggering numbers around the planet. And we’re starting to see the kind of pushback and the kind of worker fight back that we saw in Argentina after the economic crash there and that led to a whole new movement of worker-run businesses.

I’ve been tracking some of these developments, and many of them will be familiar to your viewers and listeners. But just so you know, in Argentina just in the last four months, they’ve had more worker takeovers of businesses in the last four months than they had in the previous four years. And this is the country which is the leader in worker takeover of the means of production.

In the UK, you have the Visteon auto plant, which was — there were three plants spun off from Ford in 2001. The workers there got six minutes’ notice that their workplaces were closing. I mean, the Republic Windows and Doors in Chicago, they got a few days. They got six minutes in Visteon. So, hundreds of workers did a sit-in on the roof of their plant. They were hard bargaining for about ten weeks. They ended up with a severance offer that was ten times what they were initially offered. So that’s a huge victory, although there’s still a lot of mistrust between the workers and the equity fund, which they’re negotiating with, so they’re not over there.

The famous Waterford Crystal plant in Ireland, by Wedgwood China, owned by Wedgwood China, was occupied by seven weeks earlier this year. It had been taken over by a US private equity firm. So there’s a lot going on in Europe around the foreign takeover of their production capacity.

I mentioned in Canada there have been auto plant occupations.

In France, there’s been this wave of bossnappings, where workers have been holding their bosses hostage in the workplace after seven takeovers.

JUAN GONZALEZ: Definitely don’t get that out. Don’t get that publicized.

AVI LEWIS: Well, you know, but the thing is, it’s France, so, for instance, when they held the chief executive of the plant in — the 3M plant in France, they brought himmoules et frites, they brought him mussels and French fries for dinner. So there’s — you know, there’s a level of civilization in the bossnappings there. But Caterpillar and Sony and Hewlett-Packard and other multinational corporations have faced this bossnapping technique.

And then we have in Poland, just this week, the largest coal coking producer in all of Europe. Thousands of workers bricked up the entrance to the company headquarters, because their wages had been cut.

And then we’ve seen Republic here in the United States and the Hartmarx story, this famous legendary suit maker that’s been in business more than 120 years. They made Obama’s suit that he wore on election night in Chicago. They made his tuxedo that he wore for some of the inauguration balls. And they are now facing bankruptcy at the hands of Wells Fargo, which has received $25 billion of public money.

So we see this dynamic playing out in different ways in different countries, but there’s no question that there’s an international wave of pushback. And the question is, where is it going? What forms will it take? And how do we talk about it in a way that formulates it as constructive alternatives to this economic crisis that are coming from below, because the bailouts have all been top-down?

NAOMI KLEIN: One point to just add about Wells Fargo and, you know, the suit factory in Chicago is just, you know, here we’re once again seeing just the lack of logic in the way the so-called bailout is being run, because there’s been — even though, you know, the right is constantly calling the Obama administration socialist, what we’ve actually seen is an absolute unwillingness to use the power that they should be getting by bailing out the banks to restructure the sector. And, you know, when you see these banks getting bailout money and not supporting factories that — at least in theory, this administration wants to protect manufacturing jobs. They ran a campaign saying we’re going to do this. Now, if you accepted your responsibility — the responsibility that comes from bailing out these banks, then you could actually have the power to direct those banks to lend money, to issue credit, in the interests of your other priorities, right? And so, that would be true for homeowners, and it would also be true for these factories that are being closed.

So, you know, there is this — I think it’s really important for us to understand that the Obama administration is still, you know, in the grips of this laissez-faire ideology, even as they break the core rules by intervening in the economy in such dramatic fashion. They’re intervening, but at the same time they’re saying, “Well, we don’t want to run the banks,” you know? So you have a situation like Citibank, which is worth, I think, the last I checked, $21 billion on the books, but yet $45 billion of taxpayer money has gone in. So, by all rights, American taxpayers should own Citibank more than twice over, which would mean they could direct Citibank to issue credit in the interests of taxpayers, in the interests of the public. But clearly, that’s not happening, or these factories wouldn’t be closing.

JUAN GONZALEZ: And all this money seems to be going from government guarantees or direct loans to the banks, yet you’re not seeing — you’re not seeing a situation where, for instance — now Congress has already caved in on being able to pass legislation that would allow judges to renegotiate situations where homeowners were facing foreclosure, and you’re not seeing the money go to the people who need it. It’s being spent largely, it seems, on paying off the derivative contracts that have gone bad.

NAOMI KLEIN: Well, Dick Durbin said it best. He said, you know, the banks still own this place, right? Referring to Congress and the Senate. And what’s so extraordinary about that is that Americans should own the banks, because they paid for them. Now, if that happened, then they could actually own their own government again. Wouldn’t that be revolutionary?

AMY GOODMAN: Now, maybe the missing ingredient here is the media to be asking these critical questions. I mean, who is holding those who are being bailed out and those who are bailing them out to account, Avi?

AVI LEWIS: There’s no question that there’s a huge opportunity here, which is being missed by mainstream media. But that’s not earth-shaking news to viewers and listeners of Democracy Now!

What’s interesting, though, is that workers, in many cases now, are giving the media a story. And one of the incredible things about the Republic Windows and Doors story, didn’t happen in Argentina in the wave of takeovers there; it happened subsequently, as films like The Take and others made the rounds, and people learned about what was happening there. You get worker-led constructive alternatives, which are so dramatic and so different that then they get coverage. And then you have media being forced to take notice.

Reprinted from Democracy Now!

Ταινίες & Πολυμέσα, Avi Lewis, Καναδάς, Εργασιακή Διαμάχη, Naomi Klein, New Era Windows, Εργατικός Έλεγχος, 21ος αιώνας – Εργατικός Έλεγχος στη Σύγχρονη Εποχή, Η.Π.Α., Βόρεια ΑμερικήExperienceshttp://www.democracynow.org/embed/story/2009/5/15/fire_the_boss_naomi_klein_aviΝαιΝαιNoΌχι -

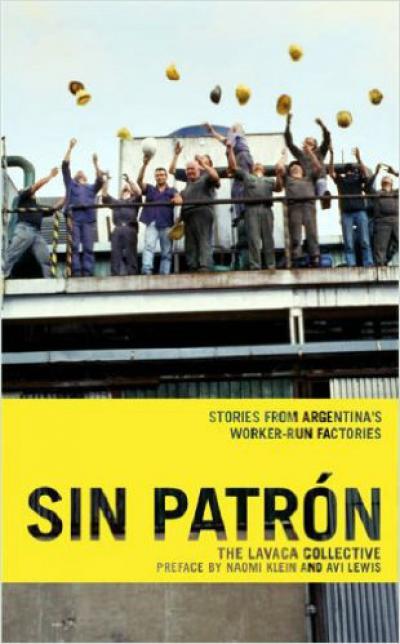

English31/12/07Foreword from the book 'Sin Patron' on the Argentinian recuperated factories.

On March 19, 2003, we were on the roof of the Zanon ceramic tile factory, filming an interview with Cepillo. He was showing us how the workers fended off eviction by armed police, defending their democratic workplace with slingshots and the little ceramic balls normally used to pound the Patagonian clay into raw material for tiles. His aim was impressive. It was the day the bombs started falling on Baghdad.

As journalists, we had to ask ourselves what we were doing there. What possible relevance could there be in this one factory at the southernmost tip of our continent, with its band of radical workers and its David and Goliath narrative, when bunker-busting apocalypse was descending on Iraq?

But we, like so many others, had been drawn to Argentina to witness firsthand an explosion of activism in the wake of its 2001 crisis-a host of dynamic new social movements that were not only advancing a bitter critique of the economic model that had destroyed their country, but were busily building local alternatives in the rubble.

There were many popular responses to the crisis, from neighborhood assemblies and barter clubs, to resurgent left-wing parties and mass movements of the unemployed, but we spent most of our year in Argentina with workers in "recovered companies." Almost entirely under the media radar, workers in Argentina have been responding to rampant unemployment and capital flight by taking over traditional businesses that have gone bankrupt and are reopening them under democratic worker management. It's an old idea reclaimed and retrofitted for a brutal new time. The principles are so simple, so elementally fair, that they seem more self-evident than radical when articulated by one of the workers in this book: "We formed the cooperative with the criteria of equal wages and making basic decisions by assembly; we are against the separation of manual and intellectual work; we want a rotation of positions and; above all, the ability to recall our elected leaders."

The movement of recovered companies is not epic in scale-some 170 companies, around 10,000 workers in Argentina. But six years on, and unlike some of the country's other new movements, it has survived and continues to build quiet strength in the midst of the country's deeply unequal "recovery." Its tenacity is a function of its pragmatism: this is a movement that is based on action, not talk. And its defining action, reawakening the means of production under worker control, while loaded with potent symbolism, is anything but symbolic. It is feeding families, rebuilding shattered pride, and opening a window of powerful possibility.

Like a number of other emerging social movements around the world, the workers in the recovered companies are rewriting the traditional script for how change is supposed to happen. Rather than following anyone's ten-point plan for revolution, the workers are darting ahead of the theory-at least, straight to the part where they get their jobs back. In Argentina, the theorists are chasing after the factory workers, trying to analyze what is already in noisy production.

These struggles have had a tremendous impact on the imaginations of activists around the world. At this point there are many more starry-eyed grad papers on the phenomenon than there are recovered companies. But there is also a renewed interest in democratic workplaces from Durban to Melbourne to New Orleans.

That said, the movement in Argentina is as much a product of the globalization of alternatives as it is one of its most contagious stories. Argentine workers borrowed the slogan, "Occupy, Resist, Produce" from Latin America's largest social movement, Brazil's Movimiento Sin Terra, in which more than a million people have reclaimed unused land and put it back into community production. One worker told us that what the movement in Argentina is doing is "MST for the cities." In South Africa, we saw a protester's T-shirt with an even more succinct summary of this new impatience: Stop Asking, Start Taking.

But as much as these similar sentiments are blossoming in different parts of the world for the same reasons, there is an urgent need to share these stories and tools of resistance even more widely. For that reason, this translation that you are holding is of tremendous importance: it's the first comprehensive portrait of Argentina's famous movement of recovered companies in English.

The book's author is the lavaca collective, itself a worker cooperative like the struggles documented here. While we were in Argentina filming our documentary, The Take, we ran into lavaca members wherever the workers' struggles led-the courts, the legislature, the streets, the factory floor. They do some of the most sophisticated engaged journalism in the world today.

And this book is classic lavaca. That means it starts with a montage-a theoretical framework that is unabashedly poetic. Then it cuts to a fight scene of the hard facts: the names, the numbers, and the m.o. behind the armed robbery that was Argentina's crisis. With the scene set, the book then zooms in to the stories of individual struggles, told almost entirely through the testimony of the workers themselves.

This approach is deeply respectful of the voices of the protagonists, while still leaving plenty of room for the authors' observations, at once playful and scathing. In this interplay between the cooperatives that inhabit the book and the one that produced it, there are a number of themes that bear mention.

First of all, there is the question of ideology. This movement is frustrating to some on the Left who feel it is not clearly anticapitalist, those who chafe at how comfortably it exists within the market economy and see worker management as merely a new form of auto-exploitation. Others see the project of cooperativism, the legal form chosen by the vast majority of the recovered companies, as a capitulation in itself-insisting that only full nationalization by the state can bring worker democracy into a broader socialist project.

In the words of the workers, and between the lines, you get a sense of these tensions and the complex relationship between various struggles and parties of the Left in Argentina. Workers in the movement are generally suspicious of being co-opted to anyone's political agenda, but at the same time cannot afford to turn down any support. More interesting by far is to see how workers in this movement are politicized by the struggle, which begins with the most basic imperative: workers want to work, to feed their families. You can see in this book how some of the most powerful new working-class leaders in Argentina today discovered solidarity on a path that started from that essentially apolitical point.

Whether you think the movement's lack of a leading ideology is a tragic weakness or a refreshing strength, this book makes clear precisely how the recovered companies challenge capitalism's most cherished ideal: the sanctity of private property.

The legal and political case for worker control in Argentina does not only rest on the unpaid wages, evaporated benefits, and emptied-out pension funds. The workers make a sophisticated case for their moral right to property-in this case, the machines and physical premises-based not just on what they're owed personally, but what society is owed. The recovered companies propose themselves as an explicit remedy to all the corporate welfare, corruption, and other forms of public subsidy the owners enjoyed in the process of bankrupting their firms and moving their wealth to safety, abandoning whole communities to the twilight of economic exclusion.

This argument is, of course, available for immediate use in the United States. But this story goes much deeper than corporate welfare, and that's where the Argentine experience will really resonate with North Americans. It's become axiomatic on the left to say that Argentina's crash was a direct result of the IMF orthodoxy imposed on the country with such enthusiasm in the neoliberal 1990s. What this book makes clear is that in Argentina, just as in the U.S. occupation of Iraq, those bromides about private sector efficiency were nothing more than a cover story for an explosion of frontier-style plunder-looting on a massive scale by a small group of elites. Privatization, deregulation, labor flexibility: these were the tools to facilitate a massive transfer of public wealth to private hands, not to mention private debts to the public purse. Like Enron traders, the businessmen who haunt the pages of this book learned the first lesson of capitalism and stopped there: greed is good, and more greed is better. As one worker says in the book, "There are guys that wake up in the morning thinking about how to screw people, and others who think, how do we rebuild this Argentina that they have torn apart?"

In the answer to that question, you can read a powerful story of transformation. This book takes as a key premise that capitalism produces and distributes not just goods and services, but identities. When the capital and its carpetbaggers had flown, what was left was not only companies that had been emptied, but a whole hollowed-out country filled with people whose identities-as workers-had been stripped away too.

As one of the organizers in the movement wrote to us, "It is a huge amount of work to recover a company. But the real work is to recover a worker and that is the task that we have just begun."

On April 17, 2003, we were on Avenida Jujuy in Buenos Aires, standing with the Brukman workers and a huge crowd of their supporters in front of a fence, behind which was a small army of police guarding the Brukman factory. After a brutal eviction, the workers were determined to get back to work at their sewing machines.

In Washington, D.C. that day, USAID announced that it had chosen Bechtel Corporation as the prime contractor for the reconstruction of Iraq's architecture. The heist was about to begin in earnest, both in the United States and in Iraq. Deliberately induced crisis was providing the cover for the transfer of billions of tax dollars to a handful of politically connected corporations.

In Argentina, they'd already seen this movie-the wholesale plunder of public wealth, the explosion of unemployment, the shredding of the social fabric, the staggering human consequences. And fifty-two seamstresses were in the street, backed by thousands of others, trying to take back what was already theirs. It was definitely the place to be.

Foreword from the book SIN PATRON: Stories from Argentina's Worker-Run Factories by La Vaca collective from Buenos Aires.

Foreword from the book SIN PATRON: Stories from Argentina's Worker-Run Factories by La Vaca collective from Buenos Aires.Reprinted from www.geo.coop

Αργεντινή, Avi Lewis, FaSinPat, Εργασιακή Διαμάχη, Naomi Klein, Ανακτημένες Επιχειρήσεις, 21ος αιώνας – Εργατικός Έλεγχος στη Σύγχρονη Εποχή, Λατινική ΑμερικήExperiencesΝαιΝαιNoΌχι -

Spanish15/08/07

En estas cortas líneas voy a reseñar una especie de evaluación de la experiencia

alcanzada en dos años de cogestión, delimitada en tres etapas con énfasis en los tópicos

de carácter socio-políticos:

a.- Primera etapa, que tuvo que ver con la construcción de la viabilidad política, centrada

en la renovación gerencial y la justicia social.

b.-Segundo etapa, enmarcada en el enfoque de cogestión con cambios en las relaciones

de producción y en una nueva prospectiva estratégica

c.- Tercera etapa, vinculada al actual debate sobre los consejos de fábrica, las empresas

socialistas y el modelo productivo rumbo al socialismo.

Todo este proceso puede ser reconstruido documentalmente, considerando múltiples

fuentes de información:

1.- La numerosas asambleas y discusiones en el seno de la comunidad alcasiana,

reseñadas en 254 HOJAS DE COGESTION, las cuales están editada en dos tomos.

2.- Las certificaciones de Junta Directiva.

3.- Las innumerables notas y comentarios de la prensa regional.

4.- Los volantes y pronunciamientos de actores oponentes del proceso cogestionario..

5.- Varias compilaciones o ensayos sobre tópicos como la reducción de la jornada de

trabajo, la división social del trabajo, la formación permanente, el debate sobre el

socialismo, los consejos de fábrica, etc..

De suyo se comprende que este proceso ha tenido un desarrollo contradictorio y diverso,

siendo una construcción colectiva tensionada por conflictos larvados, por intereses

encontrados. Pero como todo proceso revolucionario que apunta al cambio, tiene que

vencer resistencias y derrotar adversidades de diversas naturalezas.

Como un aporte para la evaluación del proceso cogestionario impulsado en la empresa ,

vamos a reseñar las diferentes etapas antes nombradas.

CARLOS LANZ RODRIGUEZ

PRESIDENTE DE CVGLALCASA

8 de Mayo 2007

Seguir la lectura en el documento adjunto:

Mayo 2007

1960-2000 – Εργατικός 'Ελεγχος ενάντια στην Καπιταλιστική Αναδιάρθρωση, Εργατικός Έλεγχος υπό τον Κρατικό Σοσιαλισμό, Alcasa, Carlos Lanz Rodriguez, Εργατικός Έλεγχος, Εργατικά Συμβούλια, Βενεζουέλα, Λατινική ΑμερικήExperiencesΝαιΝαιNoΌχι -

English31/12/05A chapter from the book "Sin Patron", by La Vaca collective from Buenos Aires.

It is one of the biggest "recuperated factories" in Argentina with exemplary worker management. It has created jobs, conquered the market, and managed to involve a whole community in its defense against repeated threats of eviction. After long legal maneuvering, a bankruptcy judge decided to hand the factory over to the Fasinpat cooperative in exchange for payment of 30,000 pesos (about $10,000) a month in taxes. It was a big step toward final expropriation and a recognition of the solid work of its 470 workers. Here is the story of this struggle, as told in La Vaca's book, "Sin Patrón" ("Without a Boss").

Zanón is one of the strangest factories to make the news. To step inside is to enter a stormy din of incomprehensible machines and meticulous robots, run by smiling people who are achieving something which some Peronists consider a crime: work.

When the din dies down somewhat, music is heard underneath. Favorite song heard at the plant comes from the Argentine band Bersuit: "Un Pacto Para Vivir" ("An Agreement to Live").

It's a strange factory. Zanón never stopped making money, but its owners touched off an enormous conflict in order to fire workers, convert the plant, and in the process further boost profits. (The case brought to mind a fable of Aesop's, written 600 years before Christ, about a hen that laid golden eggs, a tale not customarily heard in Argentine business circles.)

Previous management was supported by trade unionists. Its decision to close the plant and forsake longtime employees collided with the nearly innocent stubbornness of a lot of those employees. They couldn't believe that the company where they'd spent all of their working lives would subject them to such abuse. Luis Zanón, a man of false smiles, false intentions and false friendships (the most notorious, perhaps, with former president Carlos Menem), ended up abandoning the plant in what Judge Norma Rivero later considered an offensive lockout.

Then a judicial dance began.

(Clarification for beginners: Argentinian justice has more faces than a pair of dice. At times everything depends on chance, although it's also known that those who run the thing can use loaded dice.)

The workers resisted eviction multiple times, in the process turned Zanón into one of the strangest factories in the news. They resisted by continuing to work and by increasing production. They added to the workforce by 80 percent and created a cooperative so the court would recognize them. They call themselves FaSinPat (for Fábica Sin Patrón, or Factory Without a Boss).

Through all this they have been systematically accosted on a variety of fronts -- in the courts, by police, in politics, from organized crime. Again, the dice are the same, everything depends on whether the toss favors them. Or not.

How would they be criminalized?

"Every way, and from day one," says Raúl Godoy, a leader of the takeover. "From the beginning they accused us of being usurpers. In October 2001 we occupied the factory, in November we blocked the highway, and right away they file a suit against me. For proof they use photos on which they draw little circles to identify those they're looking for. It's funny: they use some television footage showing how there's a big crowd in the street cursing at the roadblock, with people from the University of Comahue, teachers, the Neuquén MTD [Unemployed Workers Movement], Zenón people, neighbors . . . But they filed a suit only against me as the supposed instigator. They began a most selective persecution."

Godoy is a member of the Socialist Workers Party (PTS), a force that in Neuquén came in dead last in the 2003 elections, even behind other parties of the left, unable to capitalize on the prestige of the Zanón struggle and its chief protagonist: Godoy. Even though he has won the respect of people in other parties and apolitical people, Zanón's own workers' assembly voted against whoever the workers put up as a candidate.

This is a story of pressure and persecution: A police captain named Herrera threatened Godoy, a fact the court didn't take into account. There were threats and a show of arms by the police against Godoy's little children. His house was ransacked in a robbery described by neighbors as a "commando operation."

A typical case was the kidnapping and robbery perpetrated by two convicts escaped from Prison Unit 11, whom the Río Negro daily referred to as hardened criminals. Godoy describes the leader of the two, Nelson Gómez Tejada, as "a big cheese in Neuquén." His accomplice was Juan Antonio Gómez. Both are old hands at crime, not in age (37 and 25 years, respectively) but by the length of their criminal records. It is a thin line that divides them from the police.

The pair were at the house of a Zanón worker named Miguel Vázquez. Neighbors reported suspicious activity because Gómez was on the roof cutting the electric and telephone lines. Police arrived, conversed amiably with Gómez Tejada, and went away. At the time the two were escapees from Unit 11 with warrants out for their arrest, but the police, perhaps in a humanitarian gesture, didn't want to cut short their liberty.

Armed, Gómez Tejada entered the house, held up the family and robbed the money with which the next day Zanón workers would have been paid -- more than 20,000 pesos (about $7,000). Another worker, Miguel Papatryphonos, arrived in his Fiat Uno to pick up Vázquez. Gómez took them both and also stole the Fiat Uno. A series of calls to the police led to Gómez Tejada's arrest, but a few weeks later he again escaped from Unit 11, like a kid skipping school.

"Afterwards," Godoy said, "they went to trial, but the case was dismissed because they said there was no evidence, and when they committed the robbery they were in prison!"

The stolen 20,000 pesos never surfaced. In its court briefs Río Negro's daily newspaper commented that the prosecutor "interrogated the victims thoroughly, as if they were the accused." The workers ended up hurling rotten eggs, tomatoes and gourds at the courthouse to express their opinion of the justice dispensed there.

There were tapped cell phones, telephoned threats, surveillance from mysterious automobiles, and more: the usual Argentinian thing. An attempted kidnapping of Carlos Acuña, Zanón's public relations person, failed when he screamed at the top of his voice as they tried to take him from a car. Nothing came of any complaint the workers made to the police. The courts criminalize protest, but not always crime.

Another commando operation took place in December 2003, when armed men arrived at Zanón, went to the salesroom, tied up the employees there, left a generous reminder in the form of kicks, took the day's earnings, and escaped with ease and without fear -- toward the police station.

Some of the persecution showed technological innovations, as when cell phone calls were tapped (or "punctured," in the lingering term from the days of the dictatorship). "For us it is folklore," one FaSinPat worker says. "We're in a meeting talking, they call a buddy who's outside, and let him record our voices, everything we're saying. They use your own cellular as a radio. I get a message; according to my caller ID it's a buddy of mine, but in fact they're passing along a recording of the meeting. That makes us laugh. The other day I said to a friend, throw out that cell phone, jerk, you're transmitting the whole meeting. These days this is normal as can be."

The workers have cases in the provincial high court, courts of first petition, examining magistrates, labor courts, in chamber. "You never know where the next shot's coming from," says Godoy.

In 2004 the surprise was in a Buenos Aires court considering Zanón's bankruptcy. The workers' delegation found itself face to face with Luis Zanón, who in addition to his smile had with him officials from the World Bank and the Banco Interfinanzas and administrators of the ceramics union that had been removed by the members. The banks are Zanón creditors, and the dismissed unionists are the kind who enrich themselves through good relations with management.

Godoy ponders: "This shows what we're up against. The danger is great because many planets have aligned themselves against us and, in general, against recuperated factories. They want to see you on your knees, to show that workers are good for nothing, much less to run companies."

Where is the money? Maybe it's true. Workers are no good for running businesses in ways that serve the World Bank and the Soviet-like business council. For example: the workers threw out the union bureaucracy (rather than enriching it, as Luis Zanón had), they got a factory running that the bosses had abandoned, and they didn't fire workers but instead provided work for them.

The plant has 80,000 square meters of space, occupying 9 hectares (or 22 acres) in all. On a tour of those buildings, which stretch to the horizon, one sees computerized machines with screens showing myriad bright green points, Matrix-style. Men and women focus on their own screens but have time to chat. There are giant claws, and mechanical caterpillars with pincers that grip the ceramic goods and stack them. Mechanical hoses spit pigment on the sides of the cardboard cartons. Like hands of steel, moving metal sheets pack everything. Farther on, still inside the shed, enormous funnels, four or five stories high, stir a mud-like substance. A remote-controlled cargo vehicle glides by on rails, sounding an alarm. Then is heard the sweet melody of the song "Un pacto para vivir" ("An Agreement to Live").

The sides of the cartons say FaSinPat, the ceramics' brand.

On the Web page www.fasinpat.com.ar are shown models and designs of the ceramics produced in the plant, 13 different kinds including Mapuche (the name of an indigenous people) and Obrero (worker), natural flooring tile and polished flooring tile (another 12 collections). Potentially, these products place FaSinPat at a level able to compete internationally, since Zanón, before killing the hen that laid the golden eggs, was exporting to Australia and ten European countries.

Christian Moya says one project was to concentrate on a plant exclusively to make flooring tile: "It's the biggest thing in flooring at an international level -- a polished, glossy floor. We're the one Latin American plant with three polishers, and the only one that does everything, from raw material to finished product. It's inexplicable and absurd that with that possibility they carried things to the extreme of killing it."

Some hypothesize that Luis Zanón was sending his profits abroad, others that he dumped them in the speculative financial game of the 1990s; all agree that whatever happened these were routine practices in the days of President Raúl Menem and his successor, President Fernando de la Rua.

The factory tour continues. In the administration offices there is a meeting (cell phones stay outside) and one sees posters: "We demand genuine work, they give us bullets and repression" and "Clarín [a Buenos Aires daily newspaper], journalism of the army." There are pictures of primary school children, images of people at work -- something that in broad stretches of Argentina has been turned into magic realism.

Miguel Ramírez and Reinaldo Giménez are two of the young "old hands" at the plant. Together they tell the story. Until 1998 everything was going reasonably well. "Zanón was making $44 million a year and in '94 up to $67 million," says Giménez. "But they began cutting materials and supplies, they took away half of the work, all with the union's complicity."

The Ceramic Workers and Employees Union (SOECN, for Sindicato de Obreros y Empleados Ceramistas) and the union local at Zanón were controlled by the Montes brothers, who had a sweetheart deal with management.

"Zanón was very false," Ramírez says. "He would come in a couple of times a year, tour the factory, pat someone on the back. To this guy they say: we have ways to identify those who donŒt like you." A typical tactic: "If they wanted to lay off five guys, they'd announce 20 layoffs. Then the union would intervene, fight, negotiate, and would end up saying, OK, we managed to have 15 brought back. And so they'd get rid of the five that management wanted to fire."

In 1998 the Lista Marrón (leftist, combative unionists) succeeded in throwing out the leadership of the union local.

Conditions at the factory continued to worsen, and layoffs began to play a policing role with respect to the workers.

How to organize in this atmosphere? "It occurred to us to organize a soccer league outside the factory," Carlos Acuña says. "There are 14 sections, each with a team, and each elected a delegate to go to the league meetings. We took advantage of these to talk." The clandestine mechanism served as a way to organize and communicate internally (and so did the league games).

For example, the company was talking about a crisis, but in the league meetings workers accumulated data and did the math. "What crisis, if 20 trucks are going out a day, they have 25 percent of the domestic market and export to I don't know how many countries? What crisis, if they get tax incentives in the province and loans and every kind of advantage imaginable because Zanón, in addition to everything else, was Sobisch's shadow?" Jorge Sobisch is the governor of Neuquén who sees himself as a lobbyist for the businesses.

Living the boss's way. In 2000 the situation inside Zanón was getting so bad that the company was behind in paying employees. Then, in June, 20-year-old Daniel Ferrás died in the factory of a cardiorespiratory arrest. "Now we see that the first aid was a façade, even the oxygen tube was empty," Moya says.

"They weren't providing work clothes," Ramírez says, "they weren't paying us, people were beginning to see that everything was rotten, and on top of this the thing with Daniel." That unleashed a conflict that abated only when Zanón began to regularize pay. In December of 2000 factory workers would deal a different blow, quite a feat in Argentina: they defeated the union local's leadership and made Raúl Godoy secretary general of the union. In 2001 things got worse. Ramírez recounts the sequence of events: "They laid people off, strikes began, and everything came apart."

In a few words which amount to a treatise on management and worker psychology, Giménez describes what he considers Zanón's biggest mistake: "There are people who have worked here for 20 or 25 years. People who never failed. They lived for Zanón. He would have provoked great division if he had said: I'm not paying the union people because they're lazy slackers, or for whatever reason, but he put all the other workers in the same bag. So the people with most seniority said: this swine should have paid me. I gave him my life, but he has no feeling, no compassion, it makes no difference to him."

Conflict became strike. Workers put up a tent outside the plant, started picketing, walking, taking action. In return, Luis Zanón, who was getting loans from the province to continue paying his workers, wasn't paying them. Meanwhile, the local media ran news stories about him at charity dinners in Buenos Aires with former Finance Minister Domingo Cavallo, businesswoman Amalita Fortabat, industrial magnate Franco Macri and heads of other private companies, paying $10,000 a plate to alleviate the suffering of the poor.

On December 1, 2001, in the face of what constituted abandonment on the part of management, the workers occupied the plant for good. "This triggered everything and we had to go to the hierarchical plan," Giménez said. "They made us leave. We told the managers we couldn't let things go on this way. We didn't pressure anyone. And many of us decided to stay inside. Some company guards also stayed, but they didnŒt pay them either so they ended up leaving."

"We had potluck suppers, events, anything to survive," Moya said. "But the factory was a cemetery, completely shut down."

The workers received community support -- from schools, clubs, neighbors. Inmates in the local prison sent some of their food.

They picketed but regretted it when they noticed the original protest idea was isolating them. "Those on the other side were workers, like us," one of them remembered. Typical of discussions at Zanón, some workers showed formal solidarity with the pickets but insisted on pointing out their differences. Recalls Carlos Quiñimir: "The people see that we aren't just pickets but parents with families." The bias, perhaps involuntary, isn't found only in the middle class.

Whose factory is it? The workers' weapons included megaphones, leaflets, words.

They went out and made their case to everyone who passed by. They got on buses and told their story to passengers. They set up shop in barrios to explain their situation and actions. Rather than setting up roadblocks, they leafleted people driving by. "Many stopped and took food out of their trunks for us," said Giménez.

"The solidarity was tremendous," remembers Ramírez. "They sent so much food we didn't have a place to put it all. We put together bags of it to sell for the strike fund. The community and small businesses stayed with us."

Why so much support? "We always said the factory isn't ours," Giménez said. "We're using it, but it's the community's. They'd ask us what we were doing, and we'd say we weren't intransigent pickets, with clubs and all that. We used sling-shots, at worst, and if someone [affected by the strike] had a problem or an accident we'd help him. We decided it in assembly. The guys said: We don't want to have any more roadblocks. We decided to go out and explain and explain. If no one understood what we were doing they'd think we didn't have our act together."

In December 2001 one of the marches from Zanón to the Ministry of the Interior was repressed by the police, whose officers shouted, "Get the brownshirts" (a reference to the leftist Lista Marrón unionists), so there wouldn't be any confusion about who they were after. There the workers burned the telegrams they had received from the company telling them they were fired.

En March 2002 they got the machines going again, with the idea of taking the plant public under worker control. "We know the factory is totally profitable," says Carlos Acuña, FaSinPat press officer. "We continue taking on more people, paying the utility bills, and we think that if there's an economic surplus it doesn't have to go to us, nor for the politicians, nor for the business people, but to the community."

Although they weren't crazy about the idea (because they wanted to take the company public), they formed the cooperative FaSinPat as a transitional thing, in order to take over Zanón.

The factory became a case study. "They made movies of us," Ramírez said. "Delegations came from Italy, France, Bulgaria, Germany, the United States, Spain, from everywhere."

In assembly the workers established norms of cohabitation: arrive 15 minutes before and leave 15 minutes after the established schedule, for example, so the workers can catch up on the news of the day. Moya says a worker who was stealing in the factory was fired, but another "with an addiction problem had his treatment paid for, and he kept his job."

Lunch time in the Zanón cafeteria is decided by each worker. "Everyone knows what he's responsible for," Moya says. "Some rules can be the same as the ones the company used to have, but this isn't an army camp." During lunch Godoy himself can be seen serving meat to other workers, or to surprised journalists.

And the pace of production? Quiñimir shares some maté, a popular Argentinian beverage, without which sustenance the machines in his section, carrying ceramic tiles to the baking ovens, would grind to a halt. "When we used to have a boss there could be no talking like we're doing right now," he says. "You couldn't stop even for a couple of minutes. Now you don't worry, you work conscientiously, and without a foreman who's shouting that they have to make this or that objective. There used to be very fast cycles in the ovens. Pieces arrived at the kilns every 28 minutes, when it should be every 35 minutes, as it is now."

The difference, he says, is this: "It was very easy to burn one's hands and because of the speed of the machines you couldn't stop them to make adjustments. You had to loosen them while they were going and that caused a lot of accidents. Typically, you'd lose two or three fingers."

This could mean that things didn't go at the pace that tends to be propitious in the cocaine-addict capitalism of recent decades, but the workers have increased production and profits, and also the number of workers: from 240 when the plant was taken over to 400 in 2004.

The political left, the assembly, the alternative thing. What effect has the assembly had on partisan politics? Quiñimir says: "The assembly is the main thing. The parties have a big role, but one that is subordinated to the assembly. No party says: `This is what's done, and not that.' There were some collisions because we were reluctant to have them take the lead in the conflict, but responsibilities worked themselves out there and then. Parties of the left supported us in difficult times, but we didn't make the mistake of letting them have any direct influence in exchange."

And what of Godoy, the PST (Socialist Workers Party) stalwart? "Raúl is a fellow worker, but the fact that he is also a party militant is something else," says Quiñimir. "We need each other. When there's an argument, the assembly decides, since it's the highest authority."

Alberto Esparza, who in the forgotten past was affiliated with justicialismo (a political movement founded by the late Juan Perón, a former Argentine president), favors another view. "The workers who are in politics have to get back to production," he says. "And those who are in production have to be ready to carry political placards. If no one makes the mistake, no offense intended, of asking where Raúl Godoy is. That is a reflection of the right that a caudillo [political boss] always looks for. There are at least a hundred people here who could be shop stewards in any factory."

Esparza concludes: "It can be said that the left takes the lead, that there is opposition to this capitalist system. But for me the worst thing that could happen is that it turns into a sectarian or partisan thing."

Carlos Acuña agrees: "Raúl is from a party, he can bring its proposal, and I, who am not from any party, bring my own proposals that I've discussed with my family at home. There's a vote and it's decided. That simplifies things for us, and it means that we don't have the foot of a political party at the head." Acuña acknowledges that "we've learned a whole lot from the left, or from the PTS, as they've learned a lot from us."

As an example, he notes that "you can't come in here with something far out, because it won't fly." Far out? "To want to impose a policy. To want to run the struggle. Here the struggle is run from the bottom."

Esparza summarizes another political aspect: "You can't detach yourself from society and have an aggressive, Peronist message that doesn't get to anyone." They appear to be the words of a political professional. "I'm not, but I want to leave something that's going to grow. I don't know. Kids come -- students -- and ask how we did it. The first thing we did was not respect laws. And I like to explain it in my own words. It's easy to be a party regular because you're tied to a political line they dictate to you and you're ready. Much better is what we have here, where we debate, reach consensus, and know what interests we want to defend."

Alejandro López, another worker, believes nothing will be easy. "The government has a clear policy of devotion to natural resources and repression of workers," he says, "so we have to think how to make each conflict be for society. Let's say: the problem isn't with the schools. It's also my problem, 'cause I have a 9-year-old kid. The issue of health isn't about the hospital, it's about us. And unemployment is my problem."

Esparza believes that initiatives like the Coordinating Council of Alto Valle (uniting various movements and unions) can effect the creation of what they call teeth: "We don't want to be the opposition all our lives," he says. "We have to make a move. I don't exactly know what step that is, but we have to have our act together, to be able to have our program and make a fight all the way. We workers are what make the economy run. So it's an insult that it's not us workers who decide what we want to do with our future."

López is impatient with just defending, answering, reacting. "We have to take the offensive," he says. "I surely don't know how, but it's something we just love to discuss with the workers."

"If not," Esparza says, "we're convinced that the one place where we can make decisions is in the family. And not on the social questions. That is horrible. We're doing something else: taking charge of the means of production and making it go. That, for me, is the best alternative there is."

This is the Chapter on Zanon from the book "Sin Patron", by lavaca.org.

Translated by Mark Miller, November 2005

Reprinted from Upside Down World.

Αργεντινή, FaSinPat, La Vaca, Ανακτημένες Επιχειρήσεις, Εργατική Αυτοδιαχείριση, 21ος αιώνας – Εργατικός Έλεγχος στη Σύγχρονη Εποχή, Λατινική ΑμερικήExperiencesΝαιΝαιNoΌχι